A few weeks ago, Stewart Felker wrote an article about what he suggests may be “the true most embarrassing verses in the Bible” — quoting a remark famously made by C.S. Lewis regarding Mark 13:30 (“This generation will not pass away until all these things have taken place”). What Felker has in mind, though, is a statement by Jesus about marriage and the afterlife found in Luke. In fact, when I first saw him mention it in an online discussion, I almost didn’t believe it was actually in the Bible.

The remark occurs in a well-known Synoptic pericope. To understand it, we should look at Mark’s version first. The context, chapter 12, is a loosely-connected series of sermons and other opportunities for Jesus to dispense wisdom. In vv. 18–27, some Sadducees, “who say there is no resurrection,” pose a trick question to Jesus, perhaps in the hopes of discrediting him and the Pharisaic belief in a resurrection.

The scenario they pose is one in which a widow ends up marrying seven brothers in succession due to the Mosaic law on levirate marriage. Since polyandry is not allowed in Judaism, these Sadducees demand to know which of the brothers would be married to her in the resurrection (afterlife).

The challenge is easily met by Jesus. His response is that marriage will not exist after the resurrection:

For when they rise from the dead, they neither marry nor are given in marriage¹, but are like angels in the heavens. (Mark 12:25)

Matthew (22:30) follows Mark’s text closely with no change in meaning. Luke’s version, however, changes Jesus’ response to something quite astonishing:

The sons of this age marry and are given in marriage; but those accounted worthy to obtain that age and the resurrection from the dead neither marry nor are given in marriage. Indeed they cannot die anymore, for they are equal to angels and are children of God, being sons of the resurrection. (Luke 20:34b-36)

So while Mark and Matthew describe a difference between the present age, when people marry, and the resurrection, when they do not, Luke describes present-day humanity as being divided between the “sons of this age” who marry, and “those accounted worthy to obtain resurrection” who do not marry. In other words, Luke’s plain meaning is that only those who are not married are worthy to be resurrected in the next age! As New Testament scholar David E. Aune (Notre Dame) puts it:

The correctness of this interpretation is assured by the fact that it is difficult to conceive of an act of “being counted worthy” as occurring at any time subsequent to physical death. This logion, then, reflects the view that humanity is currently divided into two classes, the “sons of this age.” who marry, and “those who are counted worthy to attain that age and the resurrection from the dead,” i.e., “sons of God” or “sons of the resurrection,” who do not marry. That is, celibacy is regarded as a prerequisite for resurrection. (p. 121)

The notion of being deemed worthy of the age to come due to one’s actions in this age is well-attested in other Jewish literature, as Felker notes, citing examples from Dale Allison. Luke makes a similar distinction in 16:8 between the “sons of this age” and the “sons of light” (righteous followers of God), who both exist in the present day. And yet, the majority of biblical scholars until recently have ignored or simply failed to notice Luke’s implications here.²

How does this fit into Luke’s overall theology? Did early Christians really believe that non-marriage was a condition for resurrection? Furthermore, what ramifications does — or should — the presence of such a teaching in the Bible have for modern Christian doctrine?

Other Lucan Peculiarities Regarding Marriage

Luke’s unusual views on marriage are also evident in what he does not say in another Synoptic passage: the teaching on divorce.

In Mark 10:2-12, Jesus is challenged by some Pharisees to say whether divorce is lawful, and he replies that it is not. Matthew (19:3-12) reworks the question to be not if but when divorce by a man is lawful—reflecting the debate between two rival rabbinical schools—and has Jesus argue in favour of the Shammai school, that it is lawful only when a sexual transgression is involved (see Catchpole).

In both Mark and Matthew, the condemnation of divorce is followed by the assertion that remarriage after a divorce amounts to adultery, although Mark has Jesus say this in private to his disciples, and Matthew uses it as Jesus’ concluding argument to the Pharisees.³

Then in the house the disciples asked him again about this matter. He said to them, “Whoever divorces his wife and marries another commits adultery against her; and if she divorces her husband and marries another, she commits adultery.” (Mark 10:10-12)

And I say to you [Pharisees], whoever divorces his wife, except for unchastity, and marries another commits adultery. (Matthew 19:9)

Luke, who, up to this point, has repeated the same pericopes as Mark and Matthew — and in the same order — skips this teaching altogether, going straight to the “suffer the children” pericope that both Mark and Matthew have after the divorce pericope.⁴ To be precise, the teaching that condemns divorce is completely absent from Luke, but the maxim condemning remarriage is retained and moved to another context.

Anyone who divorces his wife and marries another commits adultery, and whoever marries a woman divorced from her husband commits adultery. (Luke 16:18)

A reasonable inference can therefore be made that Luke has no objection to divorce. It is only remarriage that he condemns! (See Seim, Asceticism, p. 120.)

In the Matthean and Marcan passages that enjoin the reader to “take up his cross”, (Matt 10.37-38, 19.27-30; Mark 10.28-31), Jesus’ instructions are to leave one’s father, mother, sister, and brother. The equivalent passages in Luke, however, add “wife” to the list of family members who must be abandoned (Luke 14.25-27, 18.28-30). And in the Lucan version of the Great Supper — an analogy for the kingdom of God — marriage is one of the reasons that prevents guests from attending (Luke 14:20), in contrast to the Matthean version, in which the banquet itself is a wedding banquet (Matt 22:2). (Ibid.)

Disapproval of procreation is also suggested in Luke’s ominous warning to the “daughters of Jerusalem”, a passage without parallels in the other Gospels:

A great number of the people followed him, and among them were women who were beating their breasts and wailing for him. But Jesus turned to them and said, “Daughters of Jerusalem, do not weep for me, but weep for yourselves and for your children. For the days are surely coming when they will say, ‘Blessed are the barren, and the wombs that never bore, and the breasts that never nursed.’ (Luke 23:27-29)

Luke’s View of the Resurrection

Luke’s presentation of the resurrection as something that begins in the present age is also important to his position on marriage:

Indeed they cannot die anymore, for they are equal to angels and are sons of God, being sons of the resurrection. (Luke 20:36)

Whereas for Mark and Matthew, those who are resurrected will be similar to the angels in that they will not marry and procreate, Luke states that those deemed worthy of resurrection are already immortal, equal to angels (Luke’s choice of vocabulary is quite clear) and sons of God in this present life. The state of resurrection is a spiritual one that begins the moment one joins the Christian community (e.g. through baptism) and commits to celibacy.

The link between angels and asexuality is fairly clear in Judaism. For example, in 1 Enoch 15:6, the Watchers were told:

But you formerly were spiritual, living an eternal, immortal life for all the generations of the world. For this reason I did not arrange wives for you because the dwelling of the spiritual ones is in heaven.

(See Fletcher-Louis, p. 78.) 2 Baruch also describes those who are resurrected as being transformed into angels.

For in the heights of that world shall they dwell,

And they shall be made like unto the angels,

And be made equal to the stars,

And they shall be changed into every form they desire,

From beauty into loveliness,

And from light into the splendor of glory. (2 Bar. 51:10)

Again, the key difference between Luke and Mark/Matthew is that for Luke, the angelic nature of the sons of God is emphasized more strongly, and is evident already in this life. Luke also describes the kingdom of God as a present reality and not just a future one in passages such as Luke 17:20-21:

Once [Jesus] was asked by the Pharisees when the kingdom of God was coming, and he answered, “The kingdom of God is not coming with things that can be observed; nor will they say, ‘Look, here it is!’ or ‘There it is!’ For, in fact, the kingdom of God is among you.”

Luke’s position on marriage and resurrection is by no means unusual. In fact, there were numerous early Christian movements with similar views and practices.

Marriage and Marcionism

The widespread Christian movement founded by Marcion of Sinope possessed the earliest recognizable New Testament canon — ten letters of Paul’s and an early edition of Luke. The Marcionites understood Luke 20:34-36 quite literally, believing celibate asceticism to be the ideal life of a Christian. They discouraged procreation and permitted divorce. According to Tertullian and other early heresiologists, Marcion taught that sex and procreation were for the children of this world and its creator, whereas the sons of the true God did not marry.

Furthermore, Marcionites distinguished between the carnal body and the spiritual body — the type of body the angels had. The held that believers became sons of God upon baptism (cf. Gal. 3:26-29), and that Christ then dwelt inside of them. As a result, Marcionites “emphasized the fact that the life of Christ should be revealed in and through their physical bodies both ethically and ascetically” (Aune, p. 128).

Encratism and the Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles

Derived from a Greek term meaning “self-control”, encratism was an early movement that practiced celibacy, abstinence from wine, and vegetarianism. Such asceticism is a theme shared by the various apocryphal Acts of the apostles — which date to the second and third centuries — despite their theological differences. Extant translations of these documents in multiple languages despite later attempts to eradicate them attest to their early popularity.

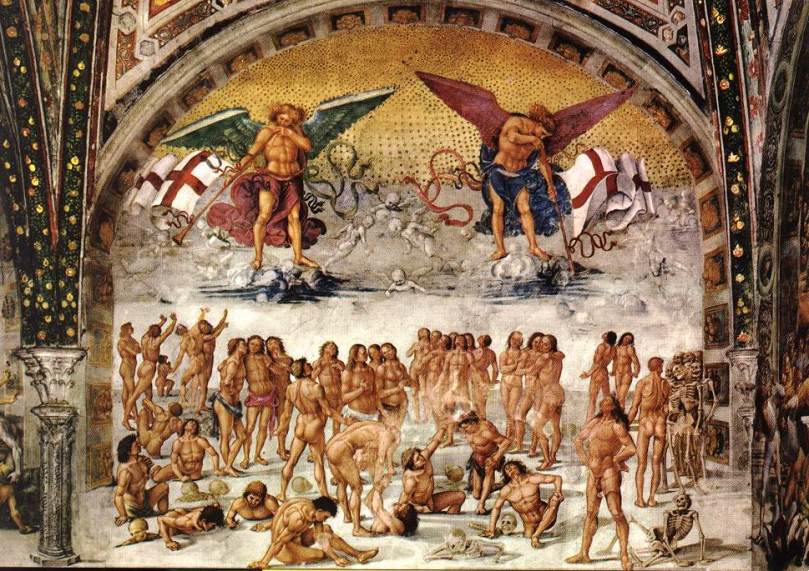

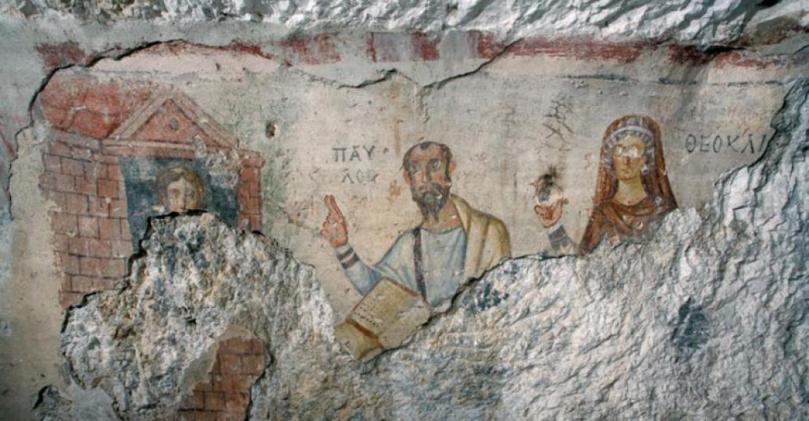

In the Acts of Paul and Thecla, Paul is accused (accurately, it seems) of teaching that only those who remain chaste will receive the resurrection. The story revolves around Paul and a woman named Thecla who spurns her fiancé to live a life of celibacy alongside the apostle. (Thecla is today regarded as a saint by the Catholic church, and two separate locations are venerated by Christians as her grave.)

A sermon delivered by Paul in verse 5 includes the following admonitions:

Blessed are those who have kept the flesh chaste, for they shall become a temple of God; blessed are the continent, for God shall speak with them; …blessed are those who have wives as not having them, for they shall experience God; blessed are those who have fear of God, for they shall become angels of God.

In one episode in the Acts of John, a young man castrates himself so he can live a chaste life in accordance with John’s teaching. Another episode features Drusiana, a woman who chooses to live a life of chastity after converting and convinces her husband to do likewise.

In the Acts of Peter, Peter repeatedly causes concubines and wives to leave their husbands, and he makes his own daughter suffer from crippling paralysis so she will not be sexually desirable to men. As part of a cruel object lesson, he actually heals her and then restores her infirmity in front of an audience!

In the Acts of Andrew, Andrew helps the newly converted Maximilla, wife of a proconsul, to remain pure from her husband’s “foul corruption” and abstain from sex so that she can be united with her “inner man”. To maintain her chastity in the face of her husband’s sexual appetite, Maximilla bribes her maidservant to take her place without her husband’s knowledge in the bed at night — an arrangement the apostle Andrew makes no objection to. Maximilla is then free to spend her nights chastely with Andrew (more on this below).

In his teaching, Andrew describes a life of marriage with intercourse as “a loathsome and unclean life”, and he teaches that “Adam died in Eve [by] consenting to her intercourse”.⁵

In the Acts of Thomas, the apostle Thomas travels to India where he similarly convinces wives to leave their husbands. On one occasion, Jesus himself appears to a couple in their bedroom on their wedding night, to explain that sex is foul and that they should never consummate their marriage.

Of all possible guests at a society wedding, an apocryphal Apostle was the worst. (Robin Lane Fox, Pagans and Christians, p. 646)

Encratism and Other New Testament Passages

Even Matthew, despite his disapproval of divorce, explicitly endorses celibacy. At the end of the divorce pericope, he inserts a discussion with the disciples not found in Mark. It starts with them telling Jesus, “If such is the case of a man with his wife, it is better not to marry.” (Matt. 19:10) Catchpole notes the incongruity here, since “nothing in verses 3-9 contains the slightest hint that avoidance of marriage is the best policy: indeed there is nothing which might give grounds even for misunderstanding.” (p. 95) This statement by the disciples, however, provides a segue for vv. 11-12, in which Jesus encourages a celibate life for anyone who can accept it — including, apparently, self-castration.

The Pauline epistles show a marked preference for celibacy and non-marriage, even if they don’t condemn marriage outright. In the famous passage in 1 Cor. 7, Paul states that widows and the unmarried should remain unmarried unless they lack the self-control to remain celibate (vv. 8-9). He wishes all Christians could be unmarried as he is (v. 7), and again advises unmarried men not to take a wife (v. 27), though the explanation given here seems to be based mainly on practical concerns (v. 28, 32-24).

More interestingly, however, is that Paul appears to approve of the encratite practice of having virgin women cohabit with chaste Christian men — even sleeping together, as Maxmilla does with the apostle Andrew — in order to live righteous lives of abstinence. In 1 Cor. 7:36, Paul advises men to marry their “virgins” if their desire toward them is too strong. But, says Paul, if they can live together without desire, they are well to do so. Modern exegetes, so separated from the context of early Christian encratism, tend to interpret Paul as talking about either fiancées or daughters, but Robin Lane Fox points out that neither of these options are satisfactory.

Paul cannot have advised fathers to marry their own daughters, nor is he obviously proposing a prolonged sexless “betrothal” between a good Christian and “his” virgin fiancée which was to last for life: “his virgin” is an odd phrase for a fiancée, and there was no reason why such a couple could not have declared a spiritual marriage, formed by their mutual consent. The older view is more likely, that the “virgins” are Christian girls whom Christian men had taken into their households. Perhaps, like Ignatius, Paul was alluding to “virgin widows,” cohabitants for the mutual care which Tertullian commended. Widows needed this care, if they were aiming to be good widows and not remarry. It is, however, possible that virgin girls were also included in his category and that Paul, looking to the end of the world, approved a relationship which subsequent councils condemned. (pp. 669-670)

Revelation also shows an interest in celibacy. According to Rev. 14, the Lamb is accompanied by 144,000 male virgins “who have not defiled themselves with women” and are the first humans to be redeemed, though the exact meaning of the passage is disputed, and some find the apparent misogyny offensive.

Luke and Syrian Asceticism

Celibacy was a major element of Syrian asceticism in the early centuries of Christianity, and Luke’s gospel was favoured for that reason (Seim, Asceticism, 115). Tatian, a second-century theologian from Syria, went so far as to forbid all marriage procreation outright, and the early Syrian church apparently required absolute abstinence as a requirement for receiving baptism (Brock, p. 7; Frend, p. 19). Baptism, of course, conferred salvation and a place in the kingdom of God.

It is no coincidence that the aforementioned Acts of Thomas were a product of the Syrian church, and that Marcionism was widespread in Syria.

The Gospel of Thomas

Another Thomasine document that appears to teach encratism is the Gospel of Thomas, an early non-canonical Gospel. It teaches the necessity of reaching a childlike state of asexuality (e.g. Thomas 37), like the state of Adam before the Fall (Thomas 85). For Thomas, the Fall corrupted the perfect human being — Adam, an androgynous being created both “male and female” (Gen. 1:27) — and split him into two sexes, an idea also found in Philo and other Jewish writers. Salvation is achieved by reversing this process. (Richardson, p. 75; Pagels, p. 480.)

On the day when you were one, you became two. (Thomas 11)

When you make the two into one…so that the male will not be male nor the female be female…then you will enter [the Father’s kingdom]. (Thomas 22)

Thomas’s understanding of salvation also has an angelomorphic element, like Luke’s. Several obscure logia seem to imply that humans have an angelic double in the heavenly realm, and one must strive to be united with that image, the “image that came into being before you” (Thomas 84). This is like the belief in an angelic double seen in Acts 12:15 — the story in which Peter escapes from jail, and the other believers assume that since he must be dead, it is “his angel” that has come knocking at the door.

In short, by linking celibacy to the resurrection and angelic immortality, Luke is promoting a widespread early Christian doctrine that influenced a wide variety of sects and religious literature.

The Bible and Modern “Biblical” Sexual Ethics

I’d like to briefly consider what effect, if any, passages like Luke 20:34-36 should have on modern Christian doctrine.

It is commonly taught from the pulpit that something called “biblical” sexual morality exists — in other words, that the Bible universally teaches a rigid code of sexual behaviour that includes a strict definition of marriage and a prohibition against all extramarital sex. Prominent evangelical theologian Wayne Grudem, in a recent tome on systematic theology, endorses the doctrine of the sufficiency of Scripture — meaning, for example, that “it is possible to find all the biblical passages that are directly relevant to the matters of marriage and divorce” (a specific example of Grudem’s) and thereby find out “what God requires us to think or to do in these areas” (p. 100).

One doesn’t have to read much of the Old Testament to have such illusions shattered. There are numerous stories of male heroes who have multiple wives and concubines (sometimes in the hundreds), who sleep with prostitutes, and who otherwise conduct themselves in a manner we would fine deplorable — without any condemnation from the text. Virginity is treated primarily as a property matter, and premarital sex is never prohibited by the Old Testament.⁶ In fact, the Song of Songs seems to celebrate it!⁷ Some laws, like levirate marriage and the prohibition on a widow remarrying a man she previously divorced, are simply too culturally bound for the modern Christian to even comprehend. Needless to say, no pastor has ever instructed the men in his congregation to have sexual congress with the wives of their deceased brothers because the Bible said so.

More often, church leaders quote from the New Testament to support their doctrines on marriage and divorce, but even here, they are inconsistent. Often, the same Protestant churches that close their doors to gay couples on the basis of Jesus’ appeal to Genesis 2:24 (“a man shall leave his parents and cleave to his wife”) welcome divorcees despite Jesus’ condemnation of divorce in the very same Synoptic passages.⁸ Churches with stricter views of divorce still exploit the adultery loophole in Matthew’s version of the divorce pericope, even though Mark’s blanket prohibition is certainly more original. Southern Baptist theologian Dan Heimbach, in a book on biblical sexual standards endorsed by Grudem, harmonizes Mark and Matthew in order to assert that “all evangelicals agree that God … allows some sort of exception [to the prohibition of divorce].” Yet when he tries figuring out just what Matthew’s exception of porneia can include and when divorce can be initiated, he finds himself in a morass of biblically defensible yet incompatible positions (pp. 203ff). The sufficiency of Scripture seems to have failed him.

Note the complete lack of attention given to Luke’s own distinctive view of marriage. Luke’s apparent endorsement of celibacy (not merely as an ethical ideal, but as a requirement for salvation!) surely must be addressed by any serious analysis of biblical ethics — even if just to dispute or debunk it — yet none of the examples I looked at did so. Heimbach’s book completely ignores the Lucan version of the resurrection question and Luke’s tacit approval of divorce. An even more comprehensive work on Christian sexual ethics by Köstenberger (also endorsed by Grudem) makes nary a mention of Luke’s views in its analysis, focusing instead on NT passages with positive views of marriage and what the conditions for permitting divorce according to Matthew are (pp. 227ff).⁹ Interestingly, Köstenberger does mention Luke’s lack of a divorce exception, but fails to divulge that Luke lacks the divorce prohibition entirely! (p. 236) He repeatedly implies, incorrectly, that both Mark and Luke give absolute prohibitions of divorce (pp. 242, 244) — a truly remarkable case of reading the text through one’s own theology. In the summary his chapter on divorce and remarriage, he summarizes four different views held by evangelical theologians — all based on compromises between Mark, Matthew, and the Pauline epistles, and none based on the actual views of Luke discussed above.

In online religious forums, I often see frank admission by more progressive Christians that their own views on sexuality (including gay marriage, extramarital sex, and divorce) do not accord with the Bible, while more conservative Christians with similar ethics will try reinterpreting the Bible to obtain justification for their views. I suspect that if such Christians took a closer look at the diversity of views endorsed by the Bible and practiced in early Christianity — including practices we would find difficult or distasteful — they would abandon the pretense of strict adherence to the Bible. They might even deal more graciously with those whose views differ.

Footnotes

¹ A note on the phrase “neither marry nor are given in marriage: “marry”, literally take a wife, describes marriage from the man’s perspective, while being “given in marriage” [i.e. by herself or by her parents] describes it from the woman’s perspective.

² A cursory check of a few commentaries shows that Stein (New American Commentary, 1992), Bock (NIV Application Commentary, 2009), Morris (Tynedale New Testament Commentary, 1988), Tannehill (Abingdon New Testament Commentary, 1996), Gundry (2011), Evans (Understanding the Bible Commentary Series, 2011), and Parsons (Paideia, 2015), among others, make no note of how Luke has reworded this passage and what its interpretational implications are. They all assume that Luke simply means to repeat what Mark and Matthew say.

³ Matthew has another version of this saying in 5:31-32 that is more difficult to interpret, and its context more closely parallels that of Luke’s version.

⁴ If Luke were being consistent in his use of Mark and Q (or Matthew, under the Farrer Hypothesis), he would have included the pericope on divorce somewhere in chapter 18 prior to verse 15. Instead, he inserts two uniquely Lucan parables at that point.

⁵ According to patristic writers, denying the salvation of Adam was commonly taught by those who also taught celibacy.

⁶ As noted in The Bible Now by Friedman and Dolansky, only the high priest of Israel was required to marry a virgin.

⁷ As David Clines wryly notes, “the lovers [in the Song of Songs] are surely not married, for otherwise she would not be living in her mother’s house and they would not be having to make excursions to the countryside for al fresco sex; on the other hand, if they are not having sex, what for goodness’ sake are they having? (“Reading the Song of Songs as a Classic”, A Critical Engagement, p. 128)

⁸ Not surprising, since divorce rates among American evangelicals are apparently as high or higher than those of the general population.

⁹ Köstenberger, who appears to have some knowledge of academic biblical studies, admits that the porneia exception might be a Matthean addition and not go back to Jesus; yet he insists that “even if this were the case, …the ‘exception clause’ would still be part of inerrant, inspired Scripture and thus authoritative for Christians today.” One wonders what view of biblical inspiration allows authors to falsely attribute teachings to Jesus, yet still holds the text to be “inerrant’.

Bibliography

Aune, David E., “Luke 20:34-36: A ‘Gnosticized’ Logion of Jesus?”, Jesus, Gospel Tradition and Paul in the Context of Jewish and Greco-Roman Antiquity: Collected Essays II (WUNT.1 303), 2013.

David R. Catchpole, “The Synoptic Divorce Material as a Traditio-Historical Problem”

Turid Karlsen Seim, “Children of the Resurrection: Perspectives on Angelic Asceticism in Luke-Acts”, Asceticism and the New Testament, 1999.

Crispin H. T. Fletcher-Louis, Luke-Acts: Angels, Christology and Soteriology, 1997.

Robin Lane Fox, Pagans and Christians, 1987.

S.P. Brock, “Early Syrian asceticism”, Numen 20/1 (Apr 1973), pp 1-19.

Frend, “The Gospel of Thomas: Is Rehabilitation Possible?”, JTS n.s. 18/1 (Apr 1967).

Cyril C. Richardson, “The Gospel of Thomas: Gnostic or Encratite?”, The Heritage of the Early Church, 1973.

Elaine H. Pagels, “Exegesis of Genesis 1 in the Gospels of Thomas and John”, JBL 118/3 (Autumn 1999).

Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Bible Doctrine, Zondervan, 1994.

Dan Heimbach, True Sexual Morality: Recovering Biblical Standards for a Culture in Crisis, Crossway Books, 2004.

Andreas J. Köstenberger, God, Marriage, and Family: Rebuilding the Biblical Foundation, Crossway Books, 2004.

Great article. Thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person

Incredibly interesting.

It’s funny how easily the Evangelists’ opinions can be harmonized without even noticing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent post. To be honest, I hadn’t given much thought to the NT endorsements of celibacy beyond the default evangelical interpretation of “no sex outside marriage”. In considering the content you outline here, however, I am compelled to ask where the theme originated and am immediately reminded of the Essene views on marriage. I’ve been drawn to see an Essenic fingerprint to the historical Jesus and this would seem to be another mark in that column. What are your thoughts on the origins of the early Christian sexual ethic – did your study here point toward any influences?

LikeLike

I would have to read a lot more about it to give a satisfactory answer, Travis. Some common trends I found though were (1) Jewish philosophical ideas about Adam’s initial sexless state (2) Platonist ascetic ideals, and (3) the imminence of the eschaton.

LikeLike

I agree with your interpretation of Luke’s view on those who are considered worthy of partaking in the resurrection & in the age to come are not married then are they?

LikeLike

Reblogged this on James' Ramblings and commented:

I am not promoting celibacy in reblogging this. I think this post does a good job in presenting diverse views on celibacy in early Christianity, and even in the New Testament.

LikeLike

Years ago, I noticed that the Synoptic Apocalypse differs in Luke regarding the gathering of the elect at the Parousia of Jesus. Compare:

I was always struck by Luke’s absence of angels to gather the elect, and I wonder if your article sheds any light on this. Perhaps since Luke viewed the elect on Earth as angels, he found it fruitless to have angels gathering up other angels.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s a fascinating observation, John!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here’s another passage that Luke changes:

In Luke’s version, the Son of Man comes not with angels, but in the glory of angels and the Father.

LikeLiked by 1 person

More and more interesting. This is worth a paper if no one has written one.

LikeLike

Sometime lurker, first-time commenter here. While I am no seminarian, nor can I read Luke in the original Greek, this

passage you quoted and the apparent interpretation feels to me like someone dropped a tense on the floor somewhere.

I read that as “here and now, people marry/are married, but, after the resurrection, those accounted worthy (requirements unspecified here) to have been resurrected, in that age, will neither marry nor die, and will be like angels.” I don’t read it as “celibacy is a necessary condition for future resurrection” at all. Which interpretation is more likely to be correct depends, I suppose, on subordinate clause structures in ancient Greek, of which I know nothing. However, my interpretation is more consistent with the parallel verses in Mark and Matthew, and Luke generally does not strike me as being in the habit of creating his own special theology. (Not to the extent that John does).

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment, Dragoness.

I’m not sure what you mean by “someone dropped a tense on the floor”.

The way Luke rewords Mark — needlessly, if he wants to say the same thing as Matthew does — seems fairly unambiguous to me. Mark says that when [after] the dead rise, they do not marry. Luke has changed the focus to who is worthy of resurrection: those who are worthy to obtain resurrection, to participate in the future age, do not marry.

As some of the sources I have cited, including Aune, point out, the logic must be that the actions that make one worthy of resurrection are fulfilled in this age. This is doubly reinforced when Luke says that the sons of this age do marry, unlike the sons of the resurrection. Do you not agree that the sons of this age and the sons of the resurrection are two contrasting groups? That the former marry, and the latter do not? Elsewhere, Luke also distinguishes between the sons of this age and the sons of light, two divisions of humanity that exist in the present day.

In short, Luke’s statement can be abbreviated as:

Those considered worthy of resurrection do not marry.

Contra-positive (necessarily also true):

Those who marry are not considered worthy of resurrection.

As the sources I cited show (especially Seim and Brock), Luke 20:35 was widely interpreted in just this manner by early Christian communities, so it is certainly not a strange interpretation from a syntactic point of view, nor a novel one historically speaking.

LikeLike

WordPress doesn’t want to let me register, I’m not sure why. However, in response to your response…

IMHO, Luke is just wordy. In translation (again, can’t read Greek here), he seems to have a much more “conversational” style than Mark or Matthew, and rambles a bit here and there. I do agree that the various passages you discuss do suggest that he believes that “the worthy” are resurrected as angels, a not uncommon belief in some Christian denominations. (And considered untrue and heretical in other denominations, go figure).

LikeLike

I read Luke’s saying that those who marry now & are given in marriage now, are no longer accounted worthy to participate in the resurrection I.e. because they married & no longer considered worthy to partake of the age to come. The apostles were called to leave everyone & everything for the sake of the kingdom. And the ten virgins who waited for the groom, where 5 were wise & 5 weren’t because they didn’t keep their oil, meaning anointing, weren’t married either. Luke’s version of the resurrection is certainly distinct.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the comment, Alison. I think your observation about the groom and ten virgins is right on point.

LikeLike

I am not sure that it necessarily follows that not marrying is the requirement for worthiness. Example:

Non professional footballers eat pies. Those counted worthy to play for Man United don’t eat pies.

On what basis were people counted worthy to play for man united? It doesnt say but we know it is footballing ability. Not simply the fact they abstain from eating pies. They abstain from pies because they have been counted worthy. ‘Now we are in the squad we don’t eat pies’.

Now obviously the question could be asked : will earing pies disqualify you or will getting married mean you aren’t actually worthy. But from the rest of Luke belief and concern for the poor seem to be the requirements for the new age.

LikeLike

What you’re suggesting is there’s an implied “also”, which is not unreasonable. “Those who are counted worthy to be footballers also don’t eat pies.” The analogy in Luke would be “Those who are counted worthy to be resurrected also don’t marry.”

I guess that’s a technical difference, but not really a practical one, because when we take the contrapositive, it means if someone does marry, then they’re not worthy of the resurrection (because they are sons of this age), just as someone eating pies must not be worthy to play for Manchester United. In either case, the worthiness and its outward sign exist in the present.

Not just concern for the poor, but being poor seems to be a requirement (see the Lazarus parable). As with the marriage issue, ascetic ideals enable one to live an angelic existence in anticipation of the resurrection — presumably like Adam before the fall, which seems to be in the background of much encratite literature.

LikeLike

I think here you are getting to the heart of the matter: Luke’s ascetic ideal may have extended into the social realm.

It seems as if to Luke a Christian anticipates the resurrection in the present by turning away from things of the world, whether they are material (riches) or social (marriage/sex).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the comment, Chuck. I think that’s a good way of summarizing it.

LikeLike

Also adding to Dragoness Eclectic comment, is there not a chance that Luke means that those counted worthy of the resurrection do not marry AFTER they have obtained that age?

‘Indeed they cannot die anymore, for they are equal to angels’

This is present tense but is referring to their future state as obviously they will die now. So ‘neither marry nor are given in marriage’ refers also to their future activities.

LikeLike

The whole point is that it’s generally assumed that’s what Luke means, but it’s not what Luke actually says. Unlike Mark and Matthew, Luke does not say those who have been resurrected will not marry. He says those who are worthy to obtain resurrection do not marry. Being worthy is a state that necessarily applies before the resurrection. So this is the plainest meaning of Luke, and any other must assume he didn’t quite say what he meant.

Furthermore, Luke’s statement that the “sons of this age” marry in contrast to the “sons of the resurrection” only makes sense if understood that these are two divisions of humanity in the writer’s present day. After all, the “sons of this age” are understood to be those who will not be resurrected, so the fact that they marry must be referring to the present time.

It’s not really that obvious, though. Luke seems to envision this angelic transformation as a present state attained by believers. He refers to believers elsewhere as “sons of light” (light being associated with angels), and as John Kesler has pointed out in these comments, reworks all the synoptic passages about angels.

Now, that’s not to say Luke thinks believers can fly around in the sky. Rather, the point seems to be that whereas ordinary people have immortality only through their offspring (the Sadducean position), believers in Jesus are immortal because they live after death and so, like angels, they have no need for marriage and procreation. (Cf. Stephen, who is transfigured as an angel in Acts 6:15 while still alive before he is stoned and the heavens open up to receive his spirit.)

Seim (see bibliography) writes:

The long and the short of it is that there’s a whole lot of ascetic idealism in Luke and the downplaying or discouragement of marriage and procreation. (One I didn’t mention was his comparison of the present age with that of Noah and Lot, when those who were marrying and being given in marriage were suddenly destroyed [Luke 17].) If none of that was there, it would be easier to assume he just meant marriage after the resurrection.

LikeLike

It’s interesting to note that Lot–and therefore the admonition to “Remember Lot’s wife” (Luke 17:32)–appears in the NT only in Luke 17 and 2 Peter 2:7. Here are a few more tidbits for you to make of what you will: In the rejection-at-Nazareth pericope (Matthew 13, Mark 6, Luke 4), only in Luke’s account is Mary not mentioned. In the temptation-by-Satan/the devil account (Matthew 4, Mark 1, Luke 4), Luke omits Matthew’s and Mark’s accounts that angels waited on Jesus. Also, Luke 11:27-28 has no parallel:

Compare Matthew 10:32-33 to Luke 12:8-9. Luke says “angels,” while Matthew says “my Father in heaven.”

LikeLike

I don’t know what to make of the “angels of God” change. It suggests to me the Son of Man instructing the celestial angels to allow believers passage through the heavens.

Luke’s dismissal of veneration for Jesus’ mother I always took to be part of the family rejection motif like in Mark, although I suppose that’s not the only way to look at it. It stands in stark contrast with the Lucan infancy narrative, which is highly pious toward Mary and must be a later addition.

LikeLike

Matthew may express a similar idea at 18:10:

LikeLike

Good find. I had some more angel material from Acts as well (since it’s closer to the “Lucan” tradition), but cut it for space.

LikeLike

What passages do you have in mind? Acts 6:15?

LikeLike

That’s one. Another is Acts 23:6-8, where τα άμφότερα (“both”) is usually incorrectly translated as “them all”, since there appears to be three things involved:

For the Sadducees say that there is no resurrection, nor angel, nor spirit; but the Pharisees acknowledge them all.

What the text actually means, according to Sullivan (2004), is that the Sadducees deny resurrection both in “the form of an angel” and in “the form of a spirit”. In other words, angelic resurrection was a specific mode of existence some Jews believed in.

LikeLike

Interesting. A check of Bible translations shows a variety, with the NRSV even using the words, “but the Pharisees acknowledge all three. “Both” certainly appears to be the correct definition–see http://biblehub.com/greek/297.htm–but I thought that Acts 19:16 might be an exception:

But here is what The Interpreter’s Bible says about Acts 19:15-16:

LikeLike

Wouldn’t you agree that all synoptics disapprove of remarriage (outside of the porneia exception in Matthew)? I just don’t see how prohibition of remarriage is unique to Luke.

LikeLike

Hi Kalif. Yes, all three synoptic Gospels disapprove of remarriage. The difference with Luke is that (1) he seems to disapprove of marriage itself, which was actually a common early Christian viewpoint, and (2) he does not forbid divorce, unlike Mark and Matthew. On the contrary, he encourages the followers of Jesus to abandon their wives. (Luke 14.25-27, 18.28-30)

LikeLike

Thanks for the response to my last comment. And yes I’m with you all the way until (2). Where do Matthew and Mark forbid divorce? They seem to forbid divorce + remarriage just like Luke does.

LikeLike

Mark forbids divorce in 10:2–9. Matthew’s parallel is in 19:3–8. Luke does not include a parallel of this discussion.

Based on how his order of content parallels that of Mark and Matthew, we should expect to find it at the end of Luke 17 or beginning of Luke 18. The pericopes that occur in Mark and Matthew right after the divorce discourse all occur in Luke in the same order in chapter 18.

LikeLike

Ah I see the disconnect in Luke now. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

No problem. The argument for Luke’s possible approval of divorce is a subtle one based on something that we would expect to find in Luke and don’t, so it’s tricky to explain.

LikeLike

This is a very interesting topic.

I like the Farrer-Goulder theory that Luke used Matthew and I think Luke rejected parts of Matthew. I also think Luke included John in Luke 1:1-4 but mostly rejected that gospel. Luke followed Mark closely from chapter 2 to near the end of chapter 9 with excursions into discourses from Matthew and moving a few similar topics together.

In the Central Section, roughly Luke 10 through the beginning of Luke 18, where Jesus is traveling to Jerusalem, Luke seems to be alluding to Moses trip to the Promised Land in Deuteronomy [per C.F. Evans, “The Central Section of St. Luke’s Gospel.” In D.E. Nineham (ed.), Studies in the Gospels: Essays in Memory of R.H. Lightfoot. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1967, pp. 37-53.]. Once Jesus reaches Jerusalem, Luke goes back to following Mark’s order.

But in the Central Section, Luke tends to take passages by topic, not by narrative order, but favors Matthew. The major agreements between Luke and Matthew against Mark that Goodacre cites are from this part of Luke though there are minor agreements with Matthew throughout Luke.

Luke seems to have had an old, worn out copy of Mark, as we see some omissions, including the Great Omission in Luke 9:18 where he jumps in mid-sentence from Mark 6:46, when he was about to be alone, the question he asked in Mark 8:27. Luke 11:16 could come from Mark 8:10 or Matthew 12:38 but Luke 11:29 is a major agreement with Matthew against Mark bring Jonah into the conversation. There are some other smaller omissions where Luke does not follow Mark’s order but seems to borrow from Matthew.

LikeLike

I found more about Acts 23:8 at the following site, which gives different interpretations of the verse: http://www.moreunseenrealm.com/?page_id=116

At that link is an explanation of τὰ ἀμφότερα which is similar to the one in The Interpreter’s Bible, quoted previously:

I also discovered a use of the word in Sirach 10:7, and “both” seems to be correct when it was written:

But the statement that Sadducees deny angels doesn’t even make sense. Angels are commonly present in the Torah, and Sadducees certainly didn’t deny their existence. In the context of the discussion of resurrection, the other interpretation fits much better. (Why even bring up whether Sadducees believe in spirits and angels?)

LikeLike

I’m inclined to agree with your/Sullivan’s interpretation, because it does seem that the reference to angel and spirit should have some connection to the subject at hand, rather than being an aside. Giving additional credence to this is comparing Acts 12:15, already discussed, with Luke’s account of the resurrection in Luke 24. I’m going to back up yo verse 12 in Acts:

Granted, the Marys are not the same, but in one instance we have Peter going to Mary’s house and presumed to be an angel (after death), while in another account, Jesus resurrects and appears to Mary et al. and is presumed to be a spirit.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Does Sullivan address the use of τα άμφότερα in Acts 19:16?

LikeLike

He does not. He does cite Viviaino and Taylor (JBL 111/3) for his argument. They have this to say on it:

Viviaino and Taylor go on to discuss these two modes of resurrection, the angelic being a “monistic anthropology” in which one’s body is transformed into a physical angelic body with various supernatural abilities, and the spiritual being a “dualistic anthropology” related to Platonism in which one’s soul simply survives the body’s death.

LikeLike

Luke 23:27-29 may be influence by Galatians 4:27 and/or Isaiah 54:1 which is quoted.

Isaiah 54:1 (NRSV)1 Sing, O barren one who did not bear; burst into song and shout, you who have not been in labor!For the children of the desolate woman will be more than the children of her that is married, says the Lord.

LikeLike

Could be, but that seems to be saying the opposite…that the barren will be blessed with children. You could make the case that Luke is both quoting and subverting (or radically reinterpreting) this passage, which is interesting.

LikeLike

This is quoted by Jesus in Matthew 19:5, but there is no Lucan counterpart, in keeping with Luke’s view on marriage. See also “Paul’s” quote of Genesis 2:24 in Ephesians 5:31.

LikeLike

There’s another use of it in 1 Cor. 6:16, but the context is prostitution. It appears that early Christians got a lot of mileage out of that verse.

LikeLike

Sorry if someone else brought this up in the comments; I skimmed through them and didn’t see it.

Your previous articles seemed to heavily argue in favor of Matthew being dependent on a proto-Luke, which was dependent on Mark. How might this affect that solution to the Synoptic Problem? (Perhaps that Matthew favored Mark instead of proto-Luke when he came across passages on marriage? Or that proto-Luke was not anti-marriage, but these are later redactions? Or that Luke came after Matthew?)

Thanks.

LikeLike

This passage doesn’t add much either way, because there are almost no minor agreements. Goulder thought the minor agreement “Finally” (ὕστερον) — a typical Matthean word — in Mt 22.27, Lk 20.32 signaled Luke copying from Matthew, but that word is also unattested for the Evangelion, so it might have been imported into Luke later.

I had the idea that the strange reaction by the disciples in Matthew’s divorce passage, assuming that marriage should be avoided, might be a response to Luke’s more stringent celibacy teaching, but I haven’t looked into it much.

LikeLike

Thank you for the response.

Sorry, by ‘Evangelion’, I assume you’re referring to the gospel text Marcion used? What evidence is there available for what his text consisted of? I was under the impression it was basically lost, and its contents barely reported second-hand by Marcion’s opponents?

LikeLike

That’s right, Marcion’s early version of Luke.

It is lost, but several scholars have made hypothetical reconstructions based on the extensive quoting and discussion of it by various patristic writers. I use BeDuhn’s mostly.

LikeLike

I never noticed this before. But it fits perfectly with Luke 14:26 (which I have noticed before) which also sounds like a call to celibacy. Hating father and mother (i.e. what they want for you, which is to get married and give them grandchildren, hating wife and children (hating the idea of having them), hating brother and sister (i.e. what they want for you, to give them nieces and nephews), and yea your own life also (the domestic life you could have had) … without these you can’t be his disciple according to that verse.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Indeed. And a great effort is made by pastors and theologians to explain why Luke doesn’t mean what he says, but really means something closer to Matthew 10:37 (“… anyone who loves their son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me”).

LikeLike

Thank you for the elaborate article..I enjoyed reading it

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oddly enough, I have seen the argument about celibacy be used… but only ever to attack homosexual or transgender peoples. That anyone who isn’t heterosexual should make a “eunuchos” (interpreted as “celibate” for the sake of this argument) of themselves for the sake of God– that homosexual people should live alone and never do anything even so much as masturbate, while the good straight people get to enjoy the love and companionship of marriage.

It makes me want to punch someone in the face.

LikeLike

I’m not sure why I should think that non-marriage is the grounds of being accounted worthy of the age to come in this passage?

So like “good students are successful in the job market” or “students given high marks are praised by others” don’t seem to carry the kind of causal relationship of the latter part to the former.

Wouldn’t the fact adultery is being warned against imply marriage is morally neutral? If Luke wanted to state marrying/having sex is an unqualified wrong, couldn’t he altered the statement to make it clearer censure of procreation? Is this a subtlety thing?

Glad God gave me a response to respond with.

Thanks for your time.

LikeLike

The most natural reading of the text is to connect the two that way, because as the text is written “being counted worthy of the resurrection” is a condition that already applies in the current age to people currently living, and it applies to those who do not marry (present tense). Furthermore, Luke divides present-day humanity into two groups: the “sons of this age” who do marry, and the “sons of the resurrection” who do not marry.

If it said, instead, “those counted worthy of the resurrection do not break my commandments, for they are sons of the resurrection,” no one would dispute that it is talking about people in the present day.

Sure, if we take it in isolation. But it is remarkable that both Mark and Matthew (who copies and amends Mark) have the prohibition of divorce pericope followed by the same pericopes in the same order — Jesus blesses the children, the rich young ruler, Jesus foretells his death, the request of James and John’s mother, etc. Luke contains, for the most part, the same pericopes in the same order as well, except that he omits the entire discussion on divorce, and moves the brief condemnation of remarriage to another passage. It is certainly worth asking why he would completely remove Christ’s prohibition of divorce from a passage of Mark he is clearly familiar with and using. My tentative answer is, “maybe he didn’t disapprove of divorce”, and this possibility is supported by historical Christian practice and numerous early Christian writings.

LikeLike

Then I could only really say is that, as the linked article notes and rebuffs, that this reading is somewhat discordant with the described scenario, and I think moreso than the comparisons offered. The set-up, I think, would generally guide the reading of the response.

LikeLike

Can I ask how this view incorporates Luke 18:19-23? It seems a natural reading of this implies one of the things which would be multiplied in this age would be wives. That is, that reading explains what “many times more” of disciples of Christ will receive “in this time”.

Luke also seems to push off eternal life to “the age to come” here, so how is that put in the tally?

Thanks for your time, God save

Felix Zamora

LikeLike

Did you give the wrong scripture reference? Luke 18:19-23 is about the rich young ruler (copied almost exactly from Mark 10:17-31), and I don’t see anything about multiple wives.

LikeLike

Yeah, sorry. I meant a little further on in 28-29?

LikeLike

29-30, gah.

LikeLike

I think he’s just talking about salvation and “treasure in heaven” as already mentioned in the same passage. Luke’s soteriology seems to understand salvation and the kingdom of heaven as something already present in the existing age, as seen in other passages.

I don’t think you can take the “much more” of v. 30 to be more of the same thing (parents, wives, etc.). As I mentioned in the article, this pericope seems to advocate abandoning one’s wife for the sake of the kingdom of God. None of the other evangelists promote this.

LikeLike

Interesting; I had not noticed this before. Luke’s view (and those like it) sound remarkably…gnostic.

It also goes to show just how much “harmonisation” of the gospels is just so much theological gymnastics.

LikeLike

Actually, here so as not to distract:

https://inpursuitoffeminity.blogspot.com/2022/04/response-to-article-about-st-paul-and.html

LikeLike

Research the Essenes. The Essenes believed in pre-destination, promoted celibacy, and conducted baptisms. They also did not believe in animal sacrifice. They were a sect of Jews along with the Sadducees, Pharisees, but they are not mentioned in any of the Gospels. Josephus and Philo both have commentary about them.

LikeLike

[…] and patriarchal propagation of one’s family name would have to be ditched in favor of a celibate itinerancy: “Rejoice that your names are written in heaven!” (Luke 10:20, cf. 14:20, 18:28-30, […]

LikeLike