A video based on this article is now available. See it here.

In 1967, inscriptions written on a crumbled plaster wall were discovered during the excavation of Tell Deir ‘Alla in Jordan. Dated to the early 8th century BCE and written in a local Canaanite dialect, the inscriptions drew great attention when their title, written in red ink, was translated and found to say “Text of Balaam son of Beor, seer of the gods.” This remarkable find provided independent attestation of local tradition about a seer named Balaam who was already well-known to us from the Bible, and deciphering the fragmentary texts has been an ongoing task of archaeologists and linguistic experts since then.

The biblical Balaam passages are not without their own difficulties. The main story of Balaam in Numbers 22–24 is contradicted by other brief references in Numbers, Deuteronomy, and Joshua, as well as three mentions of him in the New Testament. The importance of Balaam to the development of Christian theology is also remarkable, as we shall see once we untangle the development of the Balaam legend.

The Deir ‘Alla Texts

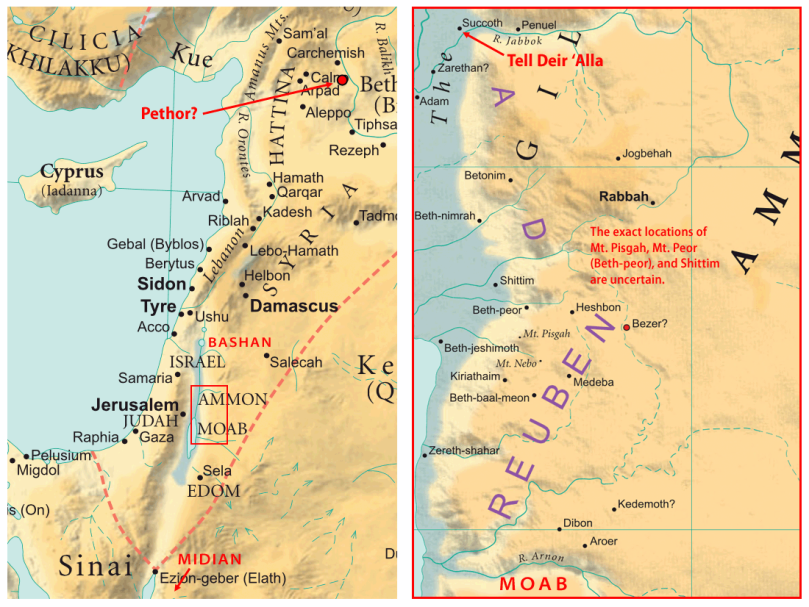

Let’s start with the archaeological data: the aforementioned texts that had been written on a wall in a religious sanctuary of some kind, located at biblical Succoth on the River Jabbok (see map below), in the region of Gilead near Ammonite territory.

There are two surviving texts. The first describes a message of doom sent from El — the high god of Canaanite religion as well as the Old Testament — to Balaam at night. A council of gods opposing El has commanded the goddess Shagar-and-Ishtar to “sew up the heavens” and produce everlasting darkness, which will be disastrous for the land and its people. After weeping and fasting for two days, Balaam rescues Shagar-and-Ishtar and dispatches powerful agents against her divine adversaries, thereby saving the land.

The second text, which is more fragmentary, describes the construction of the netherworld Sheol by El. (Summary based on Levine 141ff.)

The texts provide a fascinating look at the actual religious beliefs and scriptures of a locale the Bible considers to be part of Israel. They mention the biblical deity El, a fertility goddess, and a council of gods called the Shadday. They make no mention of Yahweh, which suggests that he was not a significant deity in Gilead, contrary to Samaria across the Jordan river. Balaam is described as a prophet who receives visions from El at night, and who delivers his oracles in a manner quite similar to some of the biblical prophets. (On this point, see Dijkstra 43-64.)

The Conquest of the Transjordan

Before we return to Balaam, there’s another biblical passage to consider. The earliest version of Israel’s conquest of the Transjordan is probably the one found at the beginning of Deuteronomy. Ch. 2 describes Israel passing peacefully through Edom and Moab into “Amorite” territory, where they fight king Sihon but are not permitted to attack the Ammonites around the River Jabbok. They continue north through Gilead and defeat king Og of Bashan, which is in the far northeast of Palestine bordering Syria. Then the Transjordan region (Gilead and Bashan) is divided amongst the tribes. The story ends with the Israelites gathered near Beth-Peor, while Moses observes the promised land across the Jordan from Mt. Pisgah. There is no mention of Balaam in this account.

The Transjordan conquest story is retold and expanded upon by another author (often regarded as the “J source” or “Yahwist”) in Numbers, and he adds several episodes that are absent from the Deuteronomist’s account. One of those is the story of Balaam.

The Main Balaam Story

If there’s one thing Balaam is most remembered for today, it’s probably his talking donkey. The story that begins in Numbers 22 is one of extremely few biblical episodes featuring articulate animals, but that’s really a minor aspect of the story. Numbers 22-24 can be summarized as follows:

The Israelites have arrived in the “plains of Moab”, having skirted the borders of Moab in the previous chapter and conquered some of the local Amorite kings. King Balak of Moab fears that he will be attacked next, so he sends for the renowned seer Balaam son of Beor to come curse the Israelites. God tells Balaam to refuse the invitation, so he does.

Balak persists and sends a second delegation. This time, Balaam is told by God to go with them but do only what God tells him. During the journey, however, an angel of Yahweh visible only to Balaam’s donkey blocks the road. After three failed attempts to make his donkey walk by hitting it, the donkey speaks and complains about Balaam’s cruel treatment. Yahweh then allows Balaam to see the angel, which gives him instructions only to speak Yahweh’s words.

Balaam then arrives at the River Arnon, the northern boundary of Moab, and meets with Balak. Balak takes him to a spot where the Israelites can be seen, but after building alters and performing sacrifices, Balaam pronounces a blessing on Israel instead of a curse. Two more times, an increasingly irate Balak takes Balaam to mountains overlooking the Israelites, and Balaam speaks blessings over Israel.

Balak gives up and tells Balaam he will receive no reward for his services. Balaam responds by giving one more oracle, this time predicting the defeat of Moab and nearby nations by a future Israelite king. Overall, the story paints a very positive picture of Balaam as a prophet and follower of the Israelite God, even if he is not an Israelite himself. This positive view of Balaam can also be found in Micah 6:5.

The Balaam story is followed a story about the Israelite men in Shittim having sexual relations with Moabite women, and Israel “yoking itself to the Baal of Peor”. The episode culminates with a terrible plague that is lifted when Pinehas, grandson of Aaron, slays a Simeonite man and his Midianite wife. (What she has to do with the Moabite women or Baal-Peor is not clear.) The Balaam story and this one are unrelated, but they were probably juxtaposed due to their common geographic location and the similarity between “Beor” and “Peor”.

Whence Cometh Balaam?

There are several difficulties with the Balaam story. The first involves his place of origin. Numbers 22:5 states that Balak “sent messengers to Balaam son of Beor, at Pethor, which is near the River, in the land of the sons of Ammo”. What that means is not obvious.

The usual view is that “the River” refers to the Euphrates, and Pethor (Hebrew Petora) must be Pitru, a city mentioned in Assyrian records. This is obviously a problem if you look at the map below. While the entire Balaam story is focused on a small region near the Dead Sea, Pitru is some 400 miles away. It defies the logic of the narrative that Balak’s delegation traversed this distance twice to exchange messages, or that Balaam undertook the journey with just a donkey and two servants (Num 22:22). This is at least a 20-day trip, and probably longer. Other problems include the fact that Pitru is actually on the Sajur River, a tributary of the Euphrates. (See Layton for a discussion of these issues and more.)

Scott C. Layton (Ibid.) concludes that Petora is actually an Aramaic title meaning “diviner”, not a toponym. Furthermore, Ammo — usually translated as “kinsfolk” — should actually be understood as Ammon, and thus Num 22:5 should be read “Balaam son of Beor the Diviner, near the river in the land of the Ammonites” — that is to say, the River Jabbok. This places Balaam in the proximity of the Israelites and Moab to begin with, and it also happens to be right where the 8th-century Balaam inscriptions were found. The author may well be referring to the very same sanctuary.

The “Elders of Midian”

Twice the story makes odd references to the “elders of Midian” as though they were residents of Moab. This makes little sense, since Midian is located far to the south, beyond Edom, and has no connection with Moab or the events in question.

Moab was in great dread of the people, because they were so numerous…. And Moab said to the elders of Midian, “This horde will now lick up all that is around us, as an ox licks up the grass of the field.” (Num 22:31, 4)

So the elders of Moab and the elders of Midian departed with the fees for divination in their hand…. (Num 22:8a)

Materially, these “elders of Midian” play absolutely no role in the story, disappearing after chapter 22. They seem to be a later insertion into the text for reasons we shall see presently.

From Hero to Villain

There is another episode in Numbers 31 — this one attributed to the Priestly writer — that portrays Balaam in a very different manner. On this occasion, 12,000 Israelites march out to war against Midian. They kill the five kings of Midian and also Balaam son of Beor (v. 8). Furthermore, Moses claims it was Balaam’s advice that caused the Midianite women to entice Israelite men to be unfaithful to God at Peor, resulting in a plague upon Israel (v. 16).

This is rather shocking, for as we just read in chapters 22-24, Balaam did no such thing. He was never in Midian, nor did he advise lascivious foreign women to lead the Israelites into idolatry. Furthermore, the original Baal-Peor episode, which immediately followed the Balaam story, concerned Moabite women rather than Midianites. However, because the two episodes sat next to each other, the author of Numbers 31 has combined them. Reshuffling the plot elements, he gives us a new story with Balaam and Midianites — a group he is strongly opposed to for some reason¹ — as antagonists. The references to the “elders of Midian” were probably added to Numbers 22 at this stage, retroactively suggesting an association between Balaam and Midian.

This version has influenced the conquest account in Joshua 13, which focuses on Balaam’s divination, rather than apostasy, as the reason for his demise:

[The Reubenites were given] …all the kingdom of King Sihon of the Amorites, who reigned in Heshbon, whom Moses defeated with the leaders of Midian, Evi and Rekem and Zur and Hur and Reba, as princes of Sihon, who lived in the land. Along with the rest of those they put to death, the Israelites also put to the sword Balaam son of Beor, who practiced divination. (Joshua 13:21b-22)

Another negative re-interpretation of the Balaam incident is found in Deut. 23:4-6. According to Van Seters (p. 129), this is a late addition that concerns the exclusion of Ammonites and Moabites from the second temple in the Persian period. It states that Balaam did curse Israel, but that God changed the curse into a blessing:

[The Ammonites and Moabites] hired against you Balaam son of Beor from Pethor of Mesopotamia to curse you. Yahweh your God was not willing to heed Balaam so that Yahweh your God changed for you the curse into blessing because Yahweh your God loves you.

Tampering with the Text

Other biblical authors continued to reshape Israelite tradition about Moab and Balaam. Joshua 24:9-10, part of Joshua’s summary of the exodus story, reads in the Hebrew MT:

Then Balak son of Zippor of Moab arose and fought with Israel. He sent and summoned Balaam son of Beor to curse them. But I was not willing to heed Balaam. He did in fact bless you, and I delivered you from his hand.

Nowhere else does the BIble say that Balak fought against Israel. Other passages explicitly reject this having happened.

Now are you any better than King Balak son of Zippor of Moab? Did he ever enter into conflict with Israel, or did he ever go to war with them? (Judges 11:25)

Furthermore, the statement that Yahweh was not willing to heed Balaam contradicts the very next statement that Balaam actually blessed Israel. And whose hand did God deliver Israel from? The syntax implies Balaam, but Balak must surely be meant. The Greek Septuagint reads a bit differently (the main difference is in bold):

And Balak the son of Sepphor, king of Moab, rose up and set himself against Israel, and he sent for Balaam to curse you. And the Lord your God was not willing to destroy you, and he blessed us with a blessing and rescued us out of their hands and gave them over.

Van Seters (p. 131) believes the text of Joshua originally read much like the Septuagint — in basic agreement with Numbers 22-24 — but that the Hebrew was later changed to match the statement in Deut. 23 that Balaam had cursed Israel.

The Ass That Spoke

Going back to the story in Numbers 22-24, we find another aspect that makes sense as a later development meant to denigrate Balaam’s character: the angel on the road and Balaam’s talking donkey. Why, having just instructed Balaam to go meet Balak, is Yahweh now angry at Balaam and impeding his progress? According to scholars, this portion is probably a late addition to the text meant to denigrate Balaam as a foreigner (cf. Van Seters 126, 131-132; Yoreh 244). Wajdenbaum (90-91) sees a parallel here with the Iliad, in which Achilles’ horse is given the ability to speak by Hera. According to Van Seters, “the talking ass story is the final degradation of the faithful prophet into a buffoon who must be instructed by his own humble donkey” (p. 132).

Balaam According to Jewish Historians

Philo, Josephus, and Pseudo-Philo emphasized the negative traditions of Balaam in their retelling of the biblical stories. To Philo, Balaam had true soothsaying skills but was not a true prophet. Josephus harmonized the discordant biblical texts by suggesting that Balaam wanted to curse Israel but could not do so, so instead he advised Balak to have Midianite women entice Israelite men away from God — twisting Numbers 24:14, “let me advise you what this people will do to your people in days to come,” to mean something else.

Rabbinical authors turned Balaam into one of several paradigmatic villains — a greedy sorcerer who tried to lead Israel astray. We’ll return to these sources a bit further on.

Balaam as Arch-Heretic in the New Testament

There are four allusions to Balaam in the New Testament. Three mention him by name, but the most important one does not.

Jude 11 — Jude 11 includes Balaam among a triumvirate of villains to whom certain heretical teachers are compared: “Woe to them! For they go the way of Cain, and abandon themselves to Balaam’s error for the sake of gain, and perish in Korah’s rebellion.”

Here, we have a portrayal of Balaam that is precisely opposite that of the God-fearing prophet in Numbers 22-24 who turned down Balak’s bribes. Jude’s Balaam is drawn from the villain of later Jewish tradition, not the original biblical version.

2 Peter 2:15-16 — 2 Peter paraphrases most of Jude. (For more on that, see my earlier article.) When he gets to Jude 11, he omits the references to Cain and Korah, focusing on Balaam to explain the behaviour of his opponents (Fornberg, 271).

They have left the straight road and have gone astray, following the road of Balaam son of Bosor, who loved the wages of doing wrong, but was rebuked for his own transgression; a speechless donkey spoke with a human voice and restrained the prophet’s madness.

The author includes Jude’s association of Balaam with greed and adds embellishments that reflect post-biblical traditions rather than the original story — for example, it is the angel that rebukes Balaam in Numbers, not the donkey.

The alteration of Balaam’s patronymic from Beor to Bosor is mystifying and has not been adequately explained. A town called Bosor in Greek (Bezer in Hebrew) appears several times in the Old Testament as a Moabite and/or Reubenite town, which fits the geography of the story. It’s hard to say if this is a coincidence.

Revelation 2:14 — Addressing the church in Pergamum, the author accuses his audience of including those who “hold to the teaching of Balaam, who taught Balak to put a stumbling block before the people of Israel, so that they would eat food sacrificed to idols and practice fornication.” Like Josephus, the author imagines that Balaam’s advice was responsible for the Baal-Peor incident. Interestingly, he highlights the eating of food sacrificed to idols as reprehensible practice some in the church are engaged in.

Some have suggested that it is the Pauline church that is targeted here. The controversy over claims of apostleship (2:2) is suggestive of the angst we find in Paul’s letters regarding his disputed apostolic credentials. Paul also suggests in 1 Corinthians 10 that there is nothing intrinsically wrong with eating meat that has been consecrated to idols. Furthermore, “fornication” was sometimes used as a broad term for practices that violated the Jewish law, and antinomianism was clearly a point of contention between Paul and his Jewish opponents. (W.C. van Manen, “Nicolaitans”, Encyclopedia Biblica; van Henten 247ff)

In summary, these three NT references use Balaam to typify people within the Christian community who spread heretical beliefs.

Balaam’s Prophecy of the Star and Sceptre

Balaam is important to early Christianity for another reason: his fourth oracle, which predicted a great Israelite ruler, was given a Messianic interpretation in the Septuagint, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the Targums. Numbers 24:17 in the Septuagint reads:

A star shall dawn out of Jacob, and a man (Hebrew: sceptre) shall rise up out of Israel. He shall crush the chiefs of Moab, and he shall plunder all Seth’s sons.

LXX Numbers 24:7 (Balaam’s third oracle) also replaces Amalekite king Agag with the eschatological foe Gog and presents a Messianic figure:

A man will come forth from his offspring, and he shall rule over many nations, and reign of him shall be exalted beyond Gog, and his reign shall be increased.

Various documents found at Qumran from around the first century BCE cited Balaam’s oracle as a prediction of the Davidic Messiah, and the association of a star with the Messiah was applied to Simon Kosiba, leader of the Jewish revolt against Rome in 132 CE who was given the name Bar Kokhba — meaning “son of the star” in Aramaic.

The Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria, who wrote in the early first century, believed Num 24:7 to be referring to a future eschatological emperor of the Jews who would rule the nations of the world. He even described this man as having a divine nature.

“A man will come forth,” says the word of God, “leading a host and warring furiously, who will subdue great and populous nations…” (Praemiis et Poenis 95)

When they have gained this unexpected liberty, those who but now were scattered in Greece and the outside world over Islands and continents will arise and post from every side with one Impulse to the one appointed place, guided in their pilgrimage by a vision divine or super human unseen by others but manifest to them as they pass from exile to their home. (Praemiis et Poenis 165)

Many of these ideas about the Messiah — a divine man and saviour associated with a star — found further expression in Christianity. It is widely believed that Matthew had Balaam’s oracle about the star of Jacob in mind when he wrote his nativity story about a star appearing at Christ’s birth. And it is perhaps no accident that Jesus’ birth was attended by Magi who knew how to interpret the star, as Balaam was regarded by early Christians as the founder of the Magi order (“Balaam”, ABD; Leemans 292-293). In other words, Balaam’s prophecy comes full circle in Matthew’s nativity story, as the star he predicted is seen by his descendants when it appears, leading them to the newborn Messiah.

Some are puzzled by Matthew’s failure to directly cite Balaam’s oracle, since he elsewhere cites the Septuagint to show its fulfillment through Christ’s birth. However, it might have been imprudent to do so here, since the name Balaam had come to symbolize heresy and apostasy in both Judaism and the nascent church. This tension is evident in other Christian writings, and some authors would misattribute Balaam’s oracle to a more suitable prophet, such as Isaiah. Justin Martyr provides an early example of this:

Another prophet, Isaiah, expressing thoughts in a different language, spoke thus: ‘A star shall rise out of Jacob, and a flower shall spring from the root of Jesse, and in His arm shall nations trust’. Indeed, a brilliant star has arisen, and a flower has sprung up from the root of Jesse—this is Christ. (Apologia 1.32)

One Final Irony

If Balaam’s star and sceptre/man came to represent Jesus in Christianity, it is curious that Balaam was often associated with Yeshu (Jesus) — a highly vilified figure — in the Talmud and rabbinical literature. One Midrash, for example, seems to reinterpret Balaam’s oracles as a condemnation of Christianity during a discussion the volume of Balaam’s voice:

And [Balaam] looked about and saw that a man, son of a woman, will arise, who seeks to make himself God and to seduce all the world without exception. Therefore, he gave strength to his voice, that all nations of the world might hear, and thus he spake: Take heed that you go not astray after that man, as it is written [Num. 23:19], God is not a man, that he should lie, and if he says that he is God, he is a liar…. (Yalkut Shimoni on Numbers 23:7)

Balaam even appears directly as a substitute name for Jesus in certain passages of the Talmud and Mishnah. For example, the Mishna (Sanhedrin 10:1) states that “all Israel have a portion in the world to come” with a few important exceptions that include “four commoners: Balaam, Doeg, Ahitophel, and Gehazi)”, and it is widely believed that Balaam (not an Israelite!) is a cipher for Jesus (Yeshu ha-Notzri), who is elsewhere listed along with Doeg, Ahitophel, and Gehazi as four wicked disciples who departed from the Torah (b. Ber 17) (see Schafer 30ff).

What a Long, Strange Trip It’s Been

Balaam’s journey through history and tradition has seen him portrayed in many different ways, with some of the main stages described below:

- At 8th-century Deir ‘Alla (Succoth) in Gilead, Balaam was remembered as a respected prophet of El, whom we recognize as one of the gods of Israel.

- According to one of the authors of Numbers, Balaam was a prophet of Yahweh/Elohim² who refused to curse Israel when asked by king Balak to do so, but blessed them instead.

- The later priestly contributors to the Pentateuch vilified Balaam as a pagan diviner who incited the Moabites and Midianites to lead Israel into idolatry.

- Post-Tanakh Jewish authors and the Qumran sect had to reconcile the negative tradition of Balaam the pagan diviner with his status as a divinely inspired prophet who foresaw the coming of the Messiah.

- Early Christian authors faced a similar dilemma, understanding the greedy and deceitful Balaam as an archetype of false teachers in the church, yet treating his words in the Septuagint as a divine prophecy of Christ’s coming.

- Finally, rabbinical Jews reinterpreted Balaam and his oracles as condemnations of Jesus and Christianity.

Footnotes

- Susan Niditch (War in the Hebrew Bible: A Study in the Ethics of Violence, pp. 79-80) suggests that the association between Moses and Midian made the latter a target of the Aaronid priests who wrote Numbers 31.

- Even within the “original” Balaam story of Numbers 22–24, there are enough discrepancies in vocabulary and narrative structure to suggest that two different versions have been merged — one in which Balaam was a follower of Elohim in opposition to Israel’s “foreign” god Yahweh, and one in which Balaam was a follower of Yahweh from the outset. The former would probably resemble the historical Balaam more closely, if such a person indeed existed. See Tzemah L. Yoreh, The First Book of God, 2010, p. 237ff.

Bibliography

Baruch A. Levine, “The Deir ‘Alla Plaster Inscriptions (The Book of Balaam, son of Beor)”, The Context of Scripture, Volume 2, 2000

Dijkstra, “Is Balaam Also among the Prophets?”, JBL 114/1

Scott C. Layton, “Whence Comes Balaam? Num 22,5 Revisited”, Biblica 73/1 (1992)

John Van Seters, “From Faithful Prophet to Villain: Observations on the Tradition History of the Balaam Story”, A Biblical Itinerary: In Search of Method, Form and Content

Philippe Wajdenbaum, Argonauts of the Desert: Structural Analysis of the Hebrew Bible, 2011

Tzemah L. Yoreh, The First Book of God, 2010

Johan Leemans, “‘To Bless with a Mouth Bent on Cursing’: Patristic Interpretations of Balaam (Num 24:17)”, The Prestige of the Pagan Prophet Balaam in Judaism, Early Christianity, and Islam, 2008

Tord Fornberg, “Balaam and 2 Peter 2:15”, The Prestige of the Pagan Prophet Balaam in Judaism, Early Christianity, and Islam, 2008

W.C. von Manen, Nicolaitans, Encyclopedia Biblica

Jan Willem van Henten, “Balaam in Revelation 2:14”, The Prestige of the Pagan Prophet Balaam in Judaism, Early Christianity, and Islam, 2008

Peter Schafer, Jesus in the Talmud, 2007

Like many other biblical stories, in your opinion is the main Balaam story also stitched together from multiple retellings of the Balaam story?

In Numbers 22:8, Balaam tells the officials of Moab, “Stay here tonight, and I will bring back word to you, just as Yahweh speaks to me,” apparently from a Yawist source. But in the very next verse, it isn’t Yahweh who comes to speak to him, but Elohim, which would make me think now we’re reading from an Elohist source. In verse 20, still reading from the Elohist source, Elohim instructs Balaam to go with the Moabites. And yet in verse 22, as soon as he has done so, Elohim’s anger burns hot against Balaam, and the reason given is ironically because he has done exactly as he was instructed! And because of that anger, who appears, blocking the way of the enlightened donkey? An angel of Yahweh, which causes me to think we’re back to reading from the Yahwist source again.

Something else I noticed while reading is something curious about how the concept biblical authors seem to have about blessings and cursings, and about how the god of the bible doesn’t seem to be completely in control of them. They seem to have a force and a power that is both independent and above the pay grade of Yahweh or Elohim to do anything about.

In verse 12, Elohim tells Balaam, “You shall not go with them; you shall not curse the people, for they are blessed.” And in the next iteration, when Elohim tells him to go, he is very careful to adjure Balaam to say only what Elohim tells him to say. The apparent purpose of the talking donkey passage seems to be to create an excuse to reiterate and emphasize the instructions in verse 34 to speak only what he is told by to speak by god.

One almost might get the impression that if Balaam were to pronounce the curse as bidden by Balak, that Yahweh/Elohim would be powerless to avert the presumably immutable force of that curse, and the Israelites would be cursed at that point, and there would be nothing that anyone, not even Yahweh or Elohim, could do about it.

It appears as though we are looking at a similar concept about blessings and cursings in the story of Jacob stealing Esau’s blessing in Genesis 27. The birthright also seems to part and parcel of the same concept, however it can be seen most clearly with the blessing. When Esau comes to his father with the meal he has prepared and Isaac discovers the ruse, he says, “Who was it then that hunted game and brought it to me, and I ate it all before you came, and I have blessed him?—yes, and blessed he shall be!” Esau pleads with his father to bless him likewise, but Isaac seems to indicate that this is impossible:

According to the authors of Genesis, they seem to think that blessings are conserved, like perhaps a dollar bill, and that blessings don’t just grow on trees. If you’ve only got one, and you give it to one of your sons, now you don’t have any dollar bills to give to your other son. Interestingly, the blessing which Isaac pronounces upon Jacob mentions both Yahweh and Elohim, however, the blessing that he pronounces upon Esau doesn’t mention the gods at all, almost like it’s a counterfeit blessing that he printed up on the spot, and probably isn’t legal tender, even though it might look enough like it to shut Esau up for the time being. Just as in the case of Balaam, once a blessing or cursing has been pronounced, it appears to be immutable.

Despite the fact that christians think they get their ideas about these things from the bible, this isn’t how I or any other christian I ever knew thought about blessings. If something like that happened in a good christian household today, well, dear ol’ dad would simply pray again that whatever he asked for previously be rescinded and scratched off the books, because of course, a blessing to modern christians is simply to beseech god to do something beneficial, and of course, the god of modern christians is too fair and nice to honor deceitful methods like those employed by Rachel and Jacob anyway. Then those concepts get read into the bible, even if they aren’t there.

LikeLike

Great comment, Ephemerol. I mentioned it briefly in footnote 2 above, but yeah, Numbers 22-24 itself seems to be a composite of two different stories, one in which Balaam is a prophet of Elohim (which explains why Balak would ask him to curse the Israelites, whose own god Yahweh is distinct from Balaam’s), and one in which Balaam is a prophet of Yahweh. Tzemah L. Yoreh has shown how the two stories can be separated out.

You’re right about the blessing and curse thing. In the Bible, blessings and curses actually work when spoken by a powerful enough priest or prophet. It is certainly weird that blessings have to be “conserved”, like in the case of Isaac who can only bless one of his sons. (What real-world father wouldn’t bless both?) It’s even weirder when you consider that Jacob cheated, and God honoured the blessing anyway as if he had no choice in the matter. (Or he approves of cheating!)

But maybe it’s not supposed to be a realistic story, so much as a folktale to illustrate the writer’s views that Edom is a cursed nation while Israel is supposed to be blessed.

Just so. Though to be fair, if you grew up in a charismatic church like I did, there were plenty of people who took blessings and curses — especially curses, for some reason — to be real phenomena that affect your health and finances. I still don’t think they could have taken these Bible stories completely literally.

LikeLike

Oh, I see. I guess I skipped over the footnotes. I guess the theological bind the textual contradictions about Balaam put people in are far more interesting, having to acknowledge him as both a bonafide prophet and wicked villain at the same time. But people never seem to have a problem bifurcating such acknowledgments into multiple mutually exclusive spheres of consideration.

Yes, I am sure, especially since Thompson, that the Jacob&Esau story is intended to be prescriptive in the sense that it is telling you that Edom is not blessed, and etiological in telling you why.

It is plausible to me that cheating is, in fact, approved of by the biblical god, and may even be seen as the reason why the previous blessings of Abraham ought to flow in the direction of Israel and not Edom. In Middle Eastern and Asian cultures today, cheating doesn’t even seem to be a thing, that’s it’s just a matter of who gets ahead and who doesn’t, and how isn’t even relevant to the equation. The one who cheats is perceived to be smart, clever, and resourceful, meanwhile the shame falls upon the one who lost out, because he is perceived to have been resting upon his rights. So I think the story would have been understood to explain that Israel is a nation of smart, resourceful people, meanwhile, Edom is a nation of “freiers” (suckers), who missed the boat way back when, and have been missing out ever since. And of course, since the re-establishment of a Jewish state, this old story has once again been given new cultural force, and especially since the Six Day War, I think Israeli Jews today, even if they don’t believe the story in a historical or religious sense, believe it in a cultural sense, and as a cultural obligation, perhaps just as much as an existential one.

Anyway, getting back to the Balaam story, it seems like Yahweh/Elohim initially told Balaam not to go because if Balaam did go and caved under pressure from Balak, and said the wrong words, then that could have put god in tight spot because his whole master plan for Israel would have been thrown into jeopardy, and that was a risk that god did not want to take. However, if god keeps being risk-averse, and telling him he can’t go, then that makes for a much less interesting story, and certainly nixes the potential for any memorable episodes featuring angels with swords or talking donkeys. So god has to take the risk, but has to engineer circumstances in order really impress upon Balaam how vitally important it is that Balaam not say the wrong words. I can just imagine Yahweh/Elohim biting his nails on the edge of his throne, petrified that from up on the overlook on Bamoth-baal, Balaam is going to pull a Maxwell Smart or George Costanza, and somehow forget and fumble the ball. But any modern theology that proposes that a “powerful” enough priest or prophet can paint god into a corner merely with the right (or wrong) incantation would have been judged heretical by Christians at least, if not Jews too, within a relatively short time after this was written. I’m curious about what the biblical authors thought was the source of power was for blessings and curses, and perhaps, for priests and prophets too. Yahweh/Elohim certainly does not appear to be that source.

I grew up in a church that had Adventist roots. We surely would have trembled at the thought of being cursed by god, but theologically, there only seem to be a handful of ways to incur that (although I suppose becoming an atheist like me would be one of them), but we didn’t think much of a curse spoken by a human, except insofar as that might cause some sort of demonic harassment which could be remedied by asking god to stop them. So in our religious milieu, blessings were ubiquitous and curses were rare and generally less potent.

LikeLike

It’s worth noting that Numbers 23:7 gives an alternate tradition about Balaam’s origins: “Then Balaam uttered his oracle, saying: ‘Balak has brought me FROM ARAM, the king of Moab from the eastern mountains…” Aram is Syria (see Judges 10:6), so it’s possible that 22:5 preserves disparate traditions about Balaam–that he was on the Euphrates and from the land of the Ammonites.

LikeLike

Yeah, I avoided getting bogged down in the “Aram” thing. Another possibility is that Succoth was an Aramean colony — there are apparently some Aramean pottery remains, and the dialect of the Balaam text has some Aramaic features — so it may be that Balaam was remembered as a prophet from Gilead but of Aramean descent.

From what I understand, Pitru (apparently a poor fit for Hebrew Petora) wasn’t Aramean but Neo-Hittite, and eventually taken over by Assyria.

LikeLike

Thanks for another interesting post. When I read the Bible as a person of faith the criticism of Balaam within the main part of the Bible story always puzzled me as it seemed unclear what Balaam had done wrong.

These stories make so much more sense once I was able to consider the possibility they were human rather than divinely inspired.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on James' Ramblings.

LikeLike

This passages is paraphrased and interpreted in Nehemiah 13:1-3:

As you hint at in the article, there is no truth to the allegation against the Moabites or Ammonites according to the narrative in Deuteronomy 2. The former are said to have sold food and water to Israel (Deut. 2:28-29), while the latter are avoided (Deut. 2:19.37). But there is another problem: the Ammonites had nothing to do with the Balaam pericope. In fact, though most versions, and I’m sorry to say the NRSV and JPS Tanakh (both old and new) are among them, “correct” Deuteronomy 23:4b (23:5b in Hebrew) to say that “they,” which in context would be the Ammonites and Moabites, hired Balaam; the text actually says that “he” hired Balaam, which would seem good circumstantial evidence that the Ammonites are a secondary addition. Two versions I know of that have this rendering are Young’s Literal Translation, and that of David Rubin, who spent 15 years translating the Tanakh into English. Here are both. If someone who reads biblical Hebrew–and Rubin presents the Hebrew text along with his translation–disagrees, please let me know.

See also the translation of Rabbi Dr. David Frankel and his very interesting article:

http://thetorah.com/the-prehistory-of-the-balaam-story/

Probably the Ammonites were lumped in with the Moabites because both are said to originate from an incestuous relationship between Lot and his daughters (Genesis 19), and both were neighbors with whom Israel fought. In fact, Judges 11, which you quote from, claims that Chemosh is the god of the Ammonites (Judges 11:24), when in fact, he was Moab’s god (Numbers 21:29, 1 Kings 11:7, 33; Jeremiah 48:1a,7; see also the Moabite Stone) and Milcom was Ammon’s (1 Kings 11:5,33; Jeremiah 49:1), which could indicate that the passage was originally a polemic against Moab which was put in its current location because of Israel’s battle with Ammon. See, for example, the annotations of The New Oxford Annotated Bible for Judges 11.

LikeLike

Interesting comment, John. The article by Dr. Frankel is good as well.

LikeLike

“They mention the biblical deity El, a fertility goddess, and a council of gods called the Shadday”

this is not true. Shaddai is the title of the goddess of fertility, and not the “advice of the gods.”

https://www.academia.edu/8554265/Shaddai_Deity_of_the_Breasts

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment. That might be what it means in the Bible, and the paper you linked is quite interesting. However, all the papers on the Deir ‘Alla Inscription I’ve read seem to agree that the Shaddayin there refers to a group of deities in some kind of assembly.

LikeLike

In the pre-biblical essay Shaddai – Shaddai was the epithet of the goddess Asherah. Ehyeh Asherah – So Yahweh’s wife introduced herself to Moses when she sent him to Egypt. (Ehyeh asher ehyeh – Exodus 3:14. – hebrew original ) Using the similarity of words (asher – Asherah), the editors denied the goddess’s involvement in the liberation operation.

The constructors of Jewish monotheism “refuted” the formula elohim = Yahweh + Asherah. They replaced it with the formula Yahweh = elohim. The word asher (the semantic meaning of this word is who, what, which) was a very powerful argument. The editors explained to the people that the ancient scribes and retellers had mixed up (asher – Asherah) due to the similarity of words. As a result, a delusional tale was born, as if Asher had freed Egyptian slaves.

The most telling example is the first commandment of the decalogue, in which the word asher (אשׁר) is present (Exodus 20: 2). Readers and scribes made a mistake. Instead of “who brought” read “Asherah brought.”

In the original story, Asherah turned Moses’ staff into a heavy Copper Serpent (so Moses could not keep him alone). The word asher in 2 Kings 18: 4 helped to refute this magical transformation. The phrase is misunderstood. Instead of “… the snake that Moses made,” they read “… the snake of Asherah made for Moses.” (the story of the reform of King Hezekiah).

The goddess was alien to extravagant antics. She did not appear to Moses in a burning bush. A burning bush is some kind of trick. It seems to me that at first the editors wrote that Asherah appeared in the senna (grass). And then the “mistake was discovered” by the ancient brainless scribes. They supposedly incorrectly rewrote the rotten papyrus.

Asherah appeared several times between the lines in chapter 21 of Genesis. Genesis 21: 1. It is possible (theoretically) to erroneously read a fragment (שׂרה כאשׁר אמר). The editors changed the name of Abraham’s wife so that by writing it resembled the name of the goddess. Because of the similarity, an error occurred in Genesis 21: 2. Instead of “giving birth to Sarah,” they understood “helped accept the birth of Asherah.” Genesis 21: 3 used both words similar to the name of the goddess (… אשׁר ילדה לו שׂרה …). Abraham erected a statue of Asherah – Genesis 21:33. So the patriarch thanked the goddess for the birth of his son.

It seems to me a fragment (דבר שׂרה אשׁת אברהם׃ …) – the end of chapter 20 of Genesis can be (theoretically) misunderstood. So, it was Asherah (the patroness of childbearing) who suspended the birth of the Philistines.

Logical analysis clearly reveals Asher in Egypt. Asherah traveled abroad – to Egypt. It was she who, at the head of the rescue team, brought Jewish slaves out of Egypt. With the help of Moses, familiar with the secrets of Egyptian magic, Asherah deceived the Egyptian priests-sorcerers. She called herself the desert goddess Kadosh. She stated that the Jews are her subjects. For centuries they did not offer her sacrifices. She asked the pharaoh to let the slaves go into the desert for a week (the distance of a three-day journey).

Asherah produced vile toads and biting insects. Pharaoh surrendered after the seventh execution. In the end, Asherah plunged Egypt into three-day darkness so that the walking Jews reached the sea before the fast pharaonic chariots. Asherah, also a goddess of the sea, parted the waters. The sea closed, blocking the road to chariots.

Amalek – the king of Edom did not let runaway slaves through his country. Moreover, he wanted to enslave them. The Jews had to accept the battle. Asherah intercepted the hired prophet. She made him speak out in favor of the Jews. Thus, the goddess deprived Edom’s army of the support of the local god.

Ashera, the goddess of heaven, stopped the sun and moon so that the Jews would win the final victory. Jews came to the sacred mountain Garizim dry land (without crossing the Jordan River).

In Samuel (the story of the journey of the Ark of the Covenant), Asherah is also disguised. The prototype of biblical history was the legend of the wedding of Yahweh and Asherah. The Philistines tried to marry the goddess to one of their gods. They brought her ark to temples – the houses of grooms.

But not one Philistine candidate Asherah liked. The goddess physically resisted the suitors who tried to rape her at night. Having bred mice, the fertility goddess forced the Philistines to let her go. They had to pay moral damage with golden mice. The mice were put in a box on the ark, in which there were no tablets.

In the end, the goddess came to Jerusalem and chose Yahweh, the patron saint of the city, as her husband. The wedding was organized by King David. Melhol, his wife, reproached her husband for participating in an orgy in honor of Asherah. The goddess, the patroness of childbearing, punished Melhol with infertility. Asherah also punished David with the death of a criminally conceived child.

During the feast of Passover, dedicated to the goddess of fertility, the ark of Lady of hosts was worn around the city, collecting donations for the goddess. Donors put precious things in the ark. Porters had no right to touch the box. Touch was considered an attempted theft.

After the collapse of the northern kingdom of Israel, the rating of the Jerusalem gods increased sharply. Porters of the ark did not have time to serve the worshipers of the goddess. King Josiah ordered the ark to be left in the temple. Let the pilgrims themselves bring their sacrifices and offerings to the temple.

In the original story, only the descendants of Israel, but not the descendants of Jacob, were in Egyptian slavery. The sons of Israel committed a series of crimes. They, in particular, sold their cousin Joseph into slavery. Joseph did not turn into slaves of the Egyptians, but robber brothers.

The gods Elohim = Yahweh + Asherah forgot about the existence of bastards. The sons of Israel also forgot about the useless gods. Lost rituals and even names. But when Asherah learned about the mass death of infants, the heart of the goddess of childbearing could not stand it.

LikeLike

Fascinating but wondering if maybe seeing a bit of Asherah behind every tree? I hope not because I have always wanted to see the female parts of the Abrahamic religions be given more attention. Goddess were pretty much found everywhere which makes sense since females are found pretty much everywhere. From Jezebel to the duplicitous spies and whores and blood-thirty female avengers, the OT is pretty anti-female.

LikeLike

I plan to write about both Jezebel and goddess worship.

LikeLike

You have really opened up the Old Testament to me. I had read the whole King James Bible twice but there’s so much as you go through the you know in your heart just isn’t humane or right and it didn’t take a genius to know that those Resurrection scenarios in the Bible seemed particularly out of accord.

But beyond that you have really linked the O.T. and N.T. to Greek and Roman thought much of which seems clear now but for some reason, the Greek stories seem to usually be better than the O.T. stories. But we would read those passages in church when bored about the sons of God and it seemed to be violently out of accord with real life but also with the fundamentalist way of thought. We don’t force people as Christians to be like Onan. For us, Onan sinned because, well you know.

I was on here earlier reviewing the Endor piece and several others and I noticed all of that. Some times magic/divination/graven images are kosher but other/most times they are not.

I would love to see you take a stab at all of the outside influences in Job and try to date that. I was reading some of it today and thinking as a lawyer, “where were you when” was an ad hominem attack by God and an exceedingly weak one at that, not to mention circular, really. It’s so clear that Job has a hokey appended epilogue.

My synopsis of Job is: “Got hotter daughters, so eh, okay.” This shows just how cherished beautiful women have always been.

Every time I read these articles, different things come to me. Just knowing other people like me were literally too intelligent for fundamentalism is consoling.

LikeLike

Jude’s Balaam is the same Balaam in Num 22-24. Just like the greedy ministers of God today.

He spoke one thing with his mouth but in his heart was something different.

From the time he knew he could not curse Israel, he should have returned home. However, he even tested God trying to find a way to appease Balak. If he could have found a way to make his money, he would.

LikeLike

Amen to that! To me its heracy to turn Heretics into a Godly prophet, Balaam served God with his lips but his heart was far from God.

I see very easy in num 22-24 the schemes and greed of Balaam.

(BTW God said “if they call you again” but he didn’t wait for that ,he went right away)

And how can one take the Bible seriously at all if he is cutting and gluing is together like he wants it and doesn’t see it as revealed by God?

LikeLike