There is probably no artifact in the Bible more famous than the Ark of the Covenant — or, to use its fullest and most ancient title, the “Ark of Yahweh Sabaoth Who Sits Enthroned upon the Cherubim”.¹ When we look at what the Bible actually says about it, we find strange tales of the Ark’s dangerous powers, conflicting stories of its construction, contradictions about its contents, and a puzzling silence about its fate. If we dig deep enough, we even find signs of alternate traditions that have been erased by later biblical editors. A thorough look at all these passages would easily fill a book, but a few issues in particular have caught my attention lately.

Though it seems like an exotic object to modern readers, portable shrines much like the ark have been found throughout Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Palestine. The Assyrians would often march to war accompanied by images of their gods carried in chariots.² Particularly reminiscent of the Israelite Ark is the pre-islamic Arab qubbah, which would be taken by the Arabs into battle, and which also contained two sacred stones for divination — not unlike the Urim and Thummim used in Jewish divination.³ And, as we shall see, the Ark was sometimes used for oracular purposes directly.

The oldest stories of the ark seem to occur in the Deuteronomistic History (Joshua through 2 Kings), with accounts of its construction and use in the Pentateuch coming somewhat later. Sometimes, identifying allusions to it can be tricky; the names of gods, both in the Bible and in other ancient texts, were often used synonymously with their cultic representations, so a reference to Yahweh or his presence could sometimes actually indicate the ark.⁴

Let’s look at the main Ark Narrative in the DH. Shortly after the battle of Jericho, the Ark disappears from the Canaanite conquest narrative. It is mentioned only once in Judges, having apparently ended up in Bethel for some reason (Judg 20:27). The real story, however, begins in 1 Samuel 4, with the Ark stationed at old Eli’s temple in Shiloh.

The Main Ark Narrative

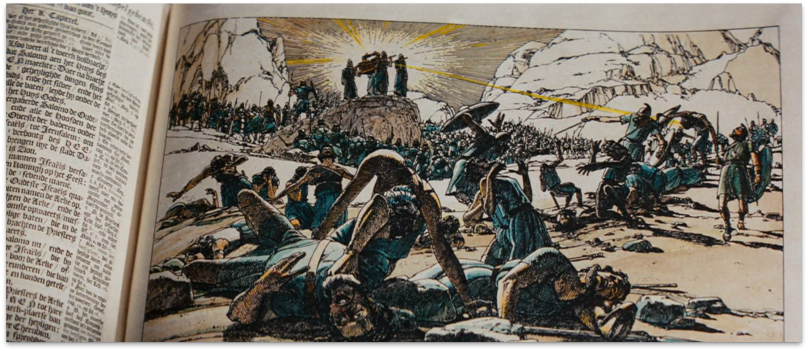

Most readers should be familiar with this tale, as it is a popular one in Sunday school. The Israelites are at war with their perennial enemies, the Philistines. The Israelites suffer a defeat; looking for solutions, they take the Ark with them to battle so that the power of Yahweh will be on their side. They lose anyway, and the ark is captured by their Philistine foes. However, the ark is too much for the Philistines to handle. When placed in the temple in Ashdod, the statue of their god Dagon ends up dismembered and decapitated. Meanwhile, the people of Ashdod are all plagued with some kind of tumour — possibly bad hemorrhoids (translations vary). They decide to send the Ark over to Gath, where another plague of tumours hits. The Ark gets sent on to Ekron, with similar results. Finally, the Philistines decide to get rid of the thing and return it to Israel, along with a gift of golden tumours and mice (!). The Ark ends up in Beth-shemesh, where the people rejoice until the Ark kills seventy of their men as well. They tell the people of Kiriath-jearim to come get it, and it ends up at “the house of Abinadab on the hill” at Kiriath-jearim. There it remains — fallen into oblivion — for the remainder of Samuel’s reign as judge, the entirety of Saul’s reign as king, and the first part of David’s reign. The Ark Narrative stops at 1 Sam 7:2 and doesn’t pick up again until 2 Sam 6.

Several decades later — 1 Sam 7.2 says 20 years, but the intervening events require a longer space of time — King David decides to go get the Ark and bring it to Jerusalem. He arrives at the house of Abinadab on the hill, puts the Ark of God on a cart, and heads for Jerusalem. Along the way, God gets mad at Abinadab’s son Uzzah for touching the Ark and strikes him dead. David gets scared and leaves the Ark at the house of Obed-edom the Gittite for three months. After that, David brings the Ark to Jerusalem amidst great festivities.

Problems with the Narrative

There are many textual oddities about the narrative. In the passages describing the Ark’s shenanigans in Philistia, the Greek LXX frequently includes details missing from the Hebrew MT, and it isn’t always clear whether this is embellishment on the Greek translator’s part or text that has gone missing from the Hebrew. For example, LXX 1 Sam 5:6 (as well as the Latin Vulgate) mentions a plague of mice in Ashdod, while the MT does not. Furthermore, all known versions of the verse in Greek and Hebrew are corrupt. According to Miller and Roberts⁵, “a comparison of MT, 4QSama, the LXX, and the other versions suggests all our extant texts are defective.” At any rate, the gift of golden mice in 6:4 makes no sense with regard to the plot unless one has read the LXX/Vulgate version of 1 Sam 5:6 about the mouse infestation. Then again, 4QSama (the Dead Sea Scrolls version) makes no mention of golden mice in 6:4, so maybe it wasn’t in there to begin with.

In this story, the Ark ends up at Kiriath-Jearim, which is an interesting town for several reasons. It was a city of the Gibeonites and Hivites, the people who made a treaty with the Israelites in Joshua 9. Kiriath-Jearim is listed in both the Benjaminite and Judahite tribal city and boundary lists, and there are textual difficulties (including name variations and glosses) in most of the verses where it is mentioned. We may also wonder why the people of Beth-shemesh were so certain that the Ark belonged here of all places. It supposedly came from the Shiloh temple, after all.

The statement that the ark was kept at Abinadab’s “house on the hill” — mentioned twice for good measure — is interesting. Names ending in –nadab appear numerous times in connection with the Levites and David: besides this Abinadab (a priest), we have David’s brother Abinadab, an Amminadab who accompanies the Ark in Chronicles, an Amminadab in David’s genealogy (1 Chr 2:10), an Amminadab in the Levite genealogy (1 Chr 6), a Nadab in the Gideonite genealogy (1 Chr 8, 9), and several others.⁶

The house on the hill seems to be a well-known hill sanctuary, probably the same place as the “mountain of Yahweh” in Gibeon (2 Sam 21:6, 9) and the “principle high place” at Gibeon in 1 Kings 3:4 where Solomon encountered Yahweh.⁷

Psalm 132 and the Ark

There is an alternate version of this story that appears in Psalm 132, a processional hymn about the Ark’s entry into Jerusalem. According to this text, the Israelites “heard of it in Ephrathah” and “found it in the fields of Jaar”, i.e. Kiriath-Jearim. One gets the impression from this psalm the Ark was a Gibeonite shrine discovered by the priesthood and brought to the temple in Jerusalem, Yahweh’s chosen location for it. Could the Ark Narrative in 1 Samuel 4–6 be a literary invention to provide a backstory for the Ark’s whereabouts in Gibeon? But there’s more…

A Secret History Uncovered

Several scholars over the years, particularly William R. Arnold, Philip R. Davies, and G. W. Ahlström, have noticed something quite interesting about the Bible’s utter silence on the Ark during Saul’s reign. Between the two halves of the Ark Narrative in 1 Sam 4–6 and 2 Sam 6 (but never during it), the text makes numerous references to an ephod — not the linen vestments (’epowd bad) that were worn for religious ceremonies, but some unknown cultic object that had to be carried by a priest (e.g. 2:28, 14:3, and 22:18), could be directly consulted as an oracle (e.g. 2:28, 23:9), and was safeguarded at the priestly city of Nob (21:9, 22:18).

The key to unlocking this riddle is in 1 Samuel 14:18. In this somewhat confusing passage, Saul is preparing for battle with the Philistines when he discovers Jonathan is missing. He then summons the priest Ahijah, great-grandson of Eli. The Hebrew reads:

Saul said to Ahijah, “Bring the ark of God here.” For at that time the ark of God went with the Israelites.

Since the Ark is supposedly holed up and forgotten in Kiriath-Jearim for the entirety of Saul’s reign, this verse has long baffled readers. The Greek LXX reads somewhat differently:

Saul said to Ahijah, “Bring the ephod,” for he bore the ephod in that day before Israel.

Biblical scholars used to prefer the LXX reading as the correct one, but Davies has shown how the case for the Hebrew being original is much stronger. Among other reasons, the principle of the lectio difficilior (more difficult reading) applies; there is no reason for a later scribe to have caused needless confusion by introducing the Ark out of thin air. Instead, it is more likely that the Greek translator has “fixed” a perceived error by substituting “Ark” with “ephod”.⁸

So the correct reading, as it stands, makes no sense within the larger narrative. But…what if there were other passages showing the Ark to be in regular use by the priests? What if a later scribe changed all the Arks to ephods, but accidentally missed one instance in 14:18? This oversight would then have been remedied by the Greek translator, but amended with an explanatory gloss (“For at that time…”) in Hebrew. Under this theory, a whole new Ark narrative emerges.

Let’s reconstruct this “secret” Ark story.

1. Part of the cultic role of the priests at Shiloh is to carry the Ark. (1 Sam. 2:28)

2. The priest Ahijah accompanies Saul to battle against the Philistines and brings the Ark. When Saul is uncertain what to do, he asks Ahijah to perform divination using the Ark. (1 Sam 14:3, 14:18)

3. David, a fugitive from Saul, comes to Nob seeking help from Ahimelech the priest. Ahimelech offers him the sword of Goliath, which is kept behind the Ark. (1 Sam 21:9)

4. Saul hears a report that the priests of Nob, including one Ahitub (a kinsman of Ahijah’s) have been assisting the fugitive David. He sends one of his officers, Doeg the Edomite, to go slaughter the priests, killing eighty-five priests associated with the Ark. (1 Sam 22:18) Only the priest Abiathar survives.

5. Abiathar has escaped with the Ark, and he brings it to David at Keilah (1 Sam 23). David is in a tight spot, so he has the Ark brought before him, and he uses it to obtain an oracle from Yahweh about whether Saul will come to Keilah, and whether David’s men will betray him.

6. Some time later, when David has become king, he again is in a tight spot; the city of Ziklag has been attacked and its people taken captive, including two of David’s wives, and Israel is on the verge of revolting. He has Abiathar bring the Ark so that he can obtain another oracle from Yahweh.

Thus, we have an older tradition that places the Ark in the priestly city of Nob. It does not get lost to the Philistines; rather, it passes into David’s possession around the same time the kingship is transferred to David.⁹ Once David rather than Saul has access to the oracle of Yahweh, the tables turn in his favour.

Why did this story get concealed? Probably because a younger tradition developed that placed the Ark in Gibeon and blamed the end of the Shilonite priesthood on the failings of Eli. The new Ark Narrative was incompatible with the old one, so earlier references to the Ark were removed (with one accidental omission). Furthermore, the writer who added the Authorized Version (as Van Der Toorn and Houtman call it) was not interested in the Ark as an object of divination or in its role in Saulide religion. For him, the loss of the Ark to the Philistines and its recovery by David provides an explanation for Yahweh’s abandonment of the Shiloh priesthood and the Philistine domination before the emergence of the Israelite kingdom. Its triumphal enshrinement in Jerusalem parallels the return of Marduk’s statue from Elam and his rise to kingship over the Babylonian gods.10 As Ahlström summarizes:

The information about the ark’s stay on Gibeonite territory indicates that this ark could not have had any connection with Shiloh. It also is noteworthy that the ark plays no part at all in the narratives about Gideon and Abimelek. This suggests that the so-called pan-Israelite ideal which occurs in the Deuteronomistic history is a literary construction. The ark narrative should be seen as a literary composition which has intentionally conflated Shiloh with Kiriath-Jearim–Jerusalem up through the story of the imprisonment and travels of the ark.11

The conclusions of Van Der Toorn and Houtman are also salient:

In the ideology of the Deuteronomist, there had never been more than one legitimate temple, and one legitimate ark—just as Yahweh was “one” Ark and temple had been connected from the beginning. In accordance with this theology, Shiloh was put forth as the precursor of Jerusalem; the author tried to demonstrate that the ark of Jerusalem had formerly been at Shiloh. The ideological angle of such historiography raises skepticism about the historical accuracy. To the Deuteronomist, however, this was a secondary concern. His aim was primarily theological; if history did not suit his purpose, he felt free to rewrite it.12

As far as the later Deuteronomistic writers are concerned, the Ark is of no importance once it is situated in the Jerusalem temple by Solomon. Its purpose in establishing Jerusalem as the seat of the Yahweh religion has been fulfilled, and it receives no further mention in the Deuteronomistic History.

One Ark or Many?

Reading through the Deuteronomistic History and finding differing tales that associate it with Bethel, Shiloh, Gilgal, Shechem, Gibeon, Nob, and Jerusalem, one might suspect that multiple Arks and similar religious objects are behind them. This is supported by both biblical and archaeological evidence — the bulls at Bethel and Dan, the divine image made by Micah (Judges 17), the “ephod” installed by Gideon at Ophrah, and more.13

Who Built the Ark?

Once the tradition of a single Ark kept in Jerusalem had been established, Jewish authors sought to explain its origins. The emerging traditions of Moses and the exodus from Egypt to explain the roots of the Hebrew religion made it only natural that Moses would be involved. We find disagreement, however, on the specifics.

In Deuteronomy 10, Moses builds the Ark himself while at Mt. Horeb, and its function is primarily to serve as a repository for the tablets of stone containing the ten commandments. As described here, it is a simple box made of acacia wood.

Yahweh said to me, “Carve out two tablets of stone like the former ones, and come up to me on the mountain, and make an ark of wood. I will write on the tablets the words that were on the former tablets, which you smashed, and you shall put them in the ark.”

So I made an ark of acacia wood, cut two tablets of stone like the former ones, and went up the mountain with the two tablets in my hand. Then he wrote on the tablets the same words as before, the ten commandments that Yahweh had spoken to you on the mountain out of the fire on the day of the assembly; and Yahweh gave them to me. So I turned and came down from the mountain, and put the tablets in the ark that I had made; and there they are, as Yahweh commanded me. (Deut 10:1–5)

Some scholars believe that the Deuteronomic writer has deliberately “de-mythologized” the Ark with his simple description of it. I’m not so sure of that; I think the Deuteronomist’s theological focus is simply different. The ultimate purpose of the Ark for him is to represent the covenant of Yahweh with Israel — hence his preferred name for it, the Ark of the Covenant. If he’s writing after the exile, he might not even know what the Ark in Jerusalem actually looked like; nor would he especially care.

In Deut 31, once Moses has finished writing out his law book, he commands the Levites to keep it next to the Ark.

Take this book of the law and put it beside the ark of the covenant of Yahweh your God; let it remain there as a witness against you. For I know well how rebellious and stubborn you are. If you already have been so rebellious toward the Lord while I am still alive among you, how much more after my death! (Deut 31:25–27)

Of course, this presupposes that the bulk of the Deuteronomistic History about Israel’s rebellion, punishment, and exile has already been written and is known to the author.

Now, the priestly author who had a hand in the book of Exodus created a much more complicated story of its construction. In Exodus 25, Yahweh gives Moses instructions for a box of acacia wood — and there, the similarity to Deuteronomy’s Ark ends. This Ark is to be of precise dimensions, overlaid with pure gold, fashioned with decorative moldings, and so on. It has an elaborate “mercy seat” with two cherubim, which functions as Yahweh’s throne or footstool. In Exodus 37, it is the artisan Bezalel who makes the Ark, rather than Moses. The work proceeds in tandem with the construction of the Tabernacle and various cultic accoutrements. Once the work is completed and the Tabernacle set up, the covenant or treaty with Yahweh is placed inside the Ark (Exod 40:20). Many of the relevant Exodus passages seem to be an expansion and retelling of the parallel passages in Deuteronomy.14

The inclusion of the mercy seat and cherubim in particular evokes Near Eastern imagery of gods with cherubim as thrones. The Ark might have functioned as a throne footstool as described in Exodus.15 However, this description does not fit with what the narratives in 1 Samuel seem to have in mind.16

The Ark Elsewhere

The near-total absence of any reference to the Ark in the prophetic literature is striking. Ezekiel spends eight chapters describing the future temple in Jerusalem, but never once mentions the Ark. The sole prophetic reference comes from Jeremiah:

And when you have multiplied and increased in the land, in those days, says Yahweh, they shall no longer say, “The ark of the covenant of Yahweh.” It shall not come to mind, or be remembered, or missed; nor shall another one be made.

However, thanks perhaps to its prominence in the Torah, the Ark of the Covenant would continue to fascinate Jewish and, eventually, Christian writers. Various traditions about the Ark would continue to develop over the centuries. We see one such variant in the New Testament, in Hebrews 9:

Behind the second curtain was a tent called the Holy of Holies. In it stood the golden altar of incense and the ark of the covenant overlaid on all sides with gold, in which there were a golden urn holding the manna, and Aaron’s rod that budded, and the tablets of the covenant; above it were the cherubim of glory overshadowing the mercy seat. (Hebrews 9:3–5a)

This description of the Ark containing a golden urn of manna and Aaron’s rod that budded does not accord with its description in the Pentateuch, which describes only the tablets being placed inside. See also 1 Kings 8:9:

There was nothing in the ark except the two tablets of stone that Moses had placed there at Horeb, where the Lord made a covenant with the Israelites, when they came out of the land of Egypt.

Both the jar of manna and Aaron’s rod are mentioned in the Pentateuch, but they are placed before the Ark rather than inside it (Exod 16:32–34; Num 17:8–10). The detail that the jar was made of gold is not found in the Hebrew, but it does appear in the Greek Septuagint of Exod 16.

The Fate of the Ark

The Bible is silent about the fate of the Ark, and there are various hypotheses as to when it could have been taken or destroyed. One would be the raids of Pharaoh Shishak, famous adopted by the plot of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Another would be the Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem in 597 BCE.17

According to some extra-biblical traditions, Jeremiah removed the Ark from the temple and hid it from the Babylonians in a cave. We know for nearly certain there was no Ark in Herod’s temple; the sacred objects found and plundered by the Romans are described by Josephus and depicted on the Arch of Titus.

Conclusions

Although there are many passages relevant to the Ark of the Covenant that I have not examined here, some conclusions can still be drawn.

1. The Ark goes by different names and fulfills different roles in the various biblical traditions that allude to it. These roles include that of war palladium, divination tool, treaty storehouse, and throne footstool for the deity.

2. The Ark is associated with different temples and sanctuaries in different texts. There may well have been numerous Arks or similar objects.

3. Redacted texts recoverable through textual criticism show that the Ark and the sanctuary at Nob were important elements of Israelite religion in Saul’s kingdom.

4. A later Deuteronomistic editor rewrote the text to accommodate a new Ark narrative that associated the Ark with the Gibeonites, King David, an idealized pan-tribal Israel, and the primacy of Jerusalem.

5. The parallel passages of the Ark’s construction in the Pentateuch were composed after the rise of “one Ark, one Yahweh” theology associated with the Jerusalem temple.

6. The Exodus account was written after the one in Deuteronomy and describes it in quite different terms than the rest of the Bible.

7. Diverse traditions about the Ark continued to develop into the Christian era, even though the physical Ark no longer existed and had long lost its religious importance.

References

- C.L. Seow, “Ark of the Covenant”, Anchor Bible Dictionary.

- Andreas Fuchs, “Assyria at War: Strategy and Conduct, The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture, 386.

- Seow.

- Ibid.

- Miller and Roberts, The Hand of the Lord, 47.

- Joseph Blenkinsopp, “Kiriath-Jearim and the Ark”, JBL 88/2 (1969), 150.

- Ibid. 151.

- Philip R. Davies, “Ark or Ephod in 1 Sam. XIV. 18?”, JTS 26/1, 1975.

- Karel Van Der Toorn and Cees Houtman, “David and the Ark”, JBL 113/2 (1994), 219.

- G. W. Ahlström, “The Travels of the Ark: A Religio-Political Composition”, JNES 43/2 (1984), 147.

- Ibid. 149.

- Van Der Toorn, 247.

- Ibid.

- Joseph Blenkinsopp, “The Narrative in Genesis–Numbers”, Those Elusive Deuteronomists (JSOT Supplement 268).

- Seow.

- Alice Wood, Of Wings and Wheels (BZAW 385, 2008), 20.

- Ibid.

Thanks again for a nice round-up! I also like the pictures you’ve chosen to illustrate the article.

LikeLike

Thanks! Thinking about the Ark got me in the mood to watch Indiana Jones, so I had to throw in some screen shots.

LikeLike

[…] There is probably no artifact in the Bible more famous than the Ark of the Covenant — or, to use its fullest and most ancient title, the “Ark of Yahweh Sabaoth Who Sits Enthroned upon the Cherubim”. [Read more] […]

LikeLike

I’ve often wondered how likely it might be that we have an etiological tale with Uzzah being struck down for reaching to stabilize the ark. If arks were covered inside and out with gold and if there were a break between the inside gold and the outside gold, then one could have what amounts to a large electrical capacitor. If insulated from being grounded, carrying it through wind driven dust could impart an electrical charge to such an ark. Having experienced powerful jolts from ground-isolated antennas that have been in dust storms, brings this to my mind.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment, Bob. The problem with those kinds of rationalist explanations (which you frequently see scientists and engineers make, but rarely theologians or Bible scholars) is that they overlook the nature of the text and its historicity. Close study of the Ark stories show that they are literary creations—based on old traditions in many cases, but also rewritten to reflect the writer’s concerns and theology. And once we understand that the priestly author’s description of an elaborate gold-inlaid shrine was invented centuries after the events in question and disagrees with earlier descriptions of a plain wooden box, we have no need to go searching for creative scientific explanations about how a box might strike a man dead.

LikeLike

I see how it could be a literary case of “friendly fire” to depict just how dangerous this god can be. No need for a criterion of embarrassment.

LikeLike

You may be interested to know that the word qubba appears in Numbers 25:8, its only appearance in the Bible, as I detail in this post: http://contradictionsinthebible.com/baal-peor-moabites-or-midianites/#comment-5313

I’ll also mention that in addition to the discrepancies which you detail in your article, which is quite good, the Bible disagrees about when the ark was constructed relative to the second set of commandments. As Deuteronomy 10, quoted above, states, the ark was already made when the second set of tablets was inscribed, which contrasts with Exodus 35:10-12, 37:1, which indicate that the ark was constructed some time after the second set of commandments was received, as narrated in Exodus 34 (see especially vv. 1, 28-29).

LikeLike

Interesting about the biblical use of the term qubba. I didn’t know that.

LikeLike

I’m reading Israel Finkelstein’s ‘The Lost Kingdom’. One interesting and relevant bit is that Shiloh shows no signs of ever having been a major sanctuary. Instead, it seems to have served as an administrative center for the local region. And then destroyed in a fire in the second half of the 11th century BCE. So the tale about the Shiloh sanctuary is pure invention, I’m guessing from a time significantly after the destruction of Shiloh. Any idea what would motivate such an invention?

LikeLike

No idea, I’m going to have to read up on that further.

LikeLike

This doesn’t change your point that the ephod is sometimes an object rather than a garment, but do you think that 1 Samuel 22:18 refers to an object? The passage refers to a “linen ephod” (cf. 1 Samuel 2:18, 2 Samuel 6:14).

An interesting point about Exodus 16:32-34 is that not only is the jar of manna said to be “before the covenant,” rather than in it, but the very mention of the covenant is anachronistic, because the covenant had not yet been given, as evidenced by Exodus 25:16: “You shall put into the ark the covenant that I shall give you.”

One such tradition is found in 2 Maccabees 2:4-5, which is considered part of “the Bible” for many Christians: “It was also in the same document that the prophet, having received an oracle, ordered that the tent and the ark should follow with him, and that he went out to the mountain where Moses had gone up and had seen the inheritance of God. Jeremiah came and found a cave-dwelling, and he brought there the tent and the ark and the altar of incense; then he sealed up the entrance.”

LikeLike

I think I meant 21:9 when I wrote 22:18.

The anachronism of the instructions for the ark being given before the covenant exists is an interesting observation.

LikeLike

Article by Yigal Levin which makes some of the same points that you do:

https://www.thetorah.com/article/the-precursors-of-the-ark

LikeLiked by 1 person